Central Park was previously home to New York’s first free Black community. What is now West 82nd to West 89th Street was previously the site of Seneca Village, a residential community made of predominantly African-American homeowners.

According to the Central Park Conservancy, Seneca Village came into existence in 1825 when landowners started to subdivide their land and sold half of their parcels to African American families. By the early 1830s, there were about 10 homes in the area.

By 1855, the community had grown to approximately 225 residents, of which two-thirds were African American. There were also Irish immigrants and individuals of German descent. All residents had to leave the Village by the end of 1857.

Cultural Significance of Seneca Village

New York abolished slavery in 1827, a few years after Seneca Village was settled. Throughout the mid-19th century, newspapers falsely reported that Seneca Village was a squatter camp with poor residents living in shanties. Research later revealed that the Village was, in fact, made up of working and middle-class property owners.

Census records show that residents were employed and worked as laborers or in service jobs, the main options for Black people at the time. Most residents lived in two-story homes and had their children enrolled in school.

A recent excavation revealed Seneca Village to be a highly-organized community

A consortium of three professors from Columbia University, New York University, and City College led an excavation on Central Park grounds to uncover details of the lost neighborhood.

Cynthia R. Copeland, an adjunct professor at New York University, told the New York Times that “the vast array of materials that we uncovered really gives us a true sense of a strong, stable community.”

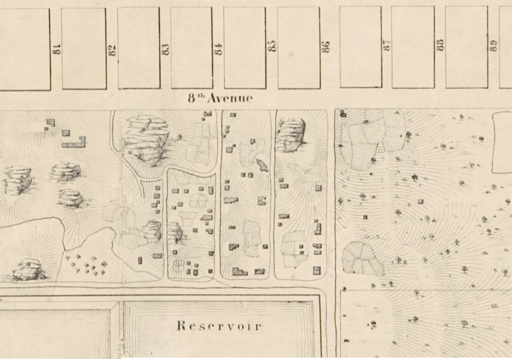

Historical maps of Seneca indicate that the community was laid out in a grid pattern and included three churches and a school. The New York Times reports Seneca was one of the “most formal, coherent Black communities we know of”.

Seneca Village was New York’s first free Black community

It’s no secret that racism and housing discrimination continued well after the abolition of slavery. Despite slavery being outlawed, Black Americans were not able to live peacefully in most areas.

Seneca’s remote location likely offered a refuge from the cruel social climate Black people had to endure. As one of the few African American enclaves at the time, the Village allowed residents to live autonomously and away from the unhealthy, crowded conditions of the city.

Research suggests that residents of Seneca Village likely had more space both in and outside of the home than many residents living in established parts of Manhattan.

As property owners, Black residents were able to vote

Seneca residents seem to have been more stable than other Black Americans living in New York. Their increased prosperity was in large part due to the fact that they owned their land.

In the early days, only property owners were able to vote. As legal homeowners, residents of Seneca could take to the polls—a right most Black people did not have at the time.

In the early 1800s, African American men living in New York had to own $250 worth of property and hold residency for at least three years to be able to vote. Of the 100 Black New Yorkers eligible to vote in 1845, 10 lived in Seneca Village.

The Village was around for a short period of just 32 years. But, as a tight-knit community formed on the heels of abolition, Seneca proved to be a stabilizing and empowering force for the Black community.

What happened to Seneca Village?

In the early 1850s, City officials started planning the creation of a large municipal park to counteract New York’s unhealthy urban conditions. The industrialization and population growth of American cities gave way for infectious diseases to spread. New York City was no exception.

Lawmakers started feeling pressure to respond and decided to acquire Seneca Village through eminent domain in 1853. Eminent domain allows the government to take private land for the public as long as the landowner is adequately compensated.

The New York State Legislature set aside 775 acres of land in Manhattan from 59th to 106th Streets to create the country’s first major public park. About 1,600 residents were displaced as a result.

Eminent domain was a common practice in the 19th century. Many of Manhattan’s streets had been built in the same way decades before.

However, many landowners, not just those in Seneca Village, argued that their land was undervalued at the time of acquisition. Many felt that they were not adequately compensated for their homes.

State of Black Homeownership in NYC

Despite Seneca’s disintegration, New York City remained a refuge for many African Americans at the time. As the first state to pass a law for the total abolition of legal slavery, New York became a popular destination to pursue a better life.

Black communities started establishing themselves in neighborhoods such as Crown Heights, Bed Stuy, Jamaica, and Harlem, many of which remain majority-Black neighborhoods today.

Although Black communities are abundant throughout New York, Black homeownership is not. Over the last 20 years, Black homeownership has declined not just in the City but throughout the country. In 2021, New York homeownership rates were 34% for Black households and 67% for White households.

Commonly regarded as the largest source of intergenerational wealth for families, it’s troubling to see such a stark contrast in rates of homeownership. According to a 2015 census report, the median net worth for white households was $139,300 compared to just $12,780 for Black households.

Experts point towards gentrification, limited housing inventory, and predatory lending as precursors of these statistics. With a history as rich as the one Black Americans have in New York, it’s important to understand what is causing low homeownership rates in the Black community.

Gentrification makes it harder for Black homeowners to keep property in the family

Tenants are arguably more susceptible to displacement because of the power landlords have to raise their rents. However, Black homeowners are not free from the pressures of gentrification.

As the price of real estate rises, communities surrounding Black homes start to change, causing Black families to feel out of place within their own communities. As a result, many choose to sell their homes and move elsewhere.

But, the transition can be bittersweet. In today’s market, sellers have to face the harsh reality that selling to the highest bidder could mean contributing towards Black displacement.

Professor of sociology and public service at New York University, Jacob Faber, told the New York Times that, “once Black people move out, it’s hard for them to get back into the neighborhood because the gentrification completely prices them out.”

Professor Faber explains that Black communities have historically been excluded from the opportunity to build wealth, which is why passing property along to family feels especially important. “There’s so much history that it’s not just a financial transaction. It’s a cultural transaction. And it’s a familial transaction,” says Professor Faber.

In the case of Shayla Mulzac, she was proud to buy into the historic Black community of Bedford Stuyvesant she’d been a part of for years. However, it is a tough realization for her as she is unsure how many more young Black homeowners will join her in the neighborhood.

Black neighborhoods suffer from higher rates of mortgage distress

Even when Black families are able to acquire a property, they’re at a higher risk of losing it. According to the latest U.S. Census Household Pulse Survey, 9.4% of Black homeowners reported they were afraid they would have to leave their homes sometime in the future, and 17.4% voiced similar concerns regarding mortgage payments.

The same survey revealed that only 3.4% of white homeowners in New York were likely to leave their homes due to foreclosure in the next two months.

Many Black neighborhoods struggling to meet mortgage payments are concentrated in eastern Brooklyn and southeast Queens—two areas previously targeted with subprime loans leading up to the 2008 financial crisis.

Evidence suggests that the subprime mortgage crisis disproportionately affected people of color by stunting new home-buying possibilities and pushing out long-time owners.

After the Great Recession, some homeowners benefited from an Obama-era program promoting loan modifications, but the majority of qualifying homeowners did not receive large-scale reductions. As a result, they remained in precarious positions and continued to be at risk of foreclosure.

Rezoning in historically Black neighborhoods leads to displacement

With such strong barriers to successful homeownership in the Black community, the only option for many Black New Yorkers is to rent. But long-term renting isn’t ideal, especially in a city as populated as NYC. As populations increase, governments rezone areas to accommodate for growth.

Grassroots organization, Churches United for Fair Housing (CUFFH), analyzed two major rezonings that took place during New York’s Bloomberg era.

Their report, “Zoning & Racialized Displacement in NYC,” revealed that the 2003 Park Slope and 2005 Williamsburg rezonings displaced thousands of Black and Latino residents as each neighborhood’s population grew.

From 2000 to 2015, the populations of Williamsburg and Greenpoint increased by over 20,000 residents. In that same period of time, about 15,000 Latino residents had left the neighborhoods.

In Park Slope, 5,000 Black and Latino households left the community from 2000-2013, despite the neighborhood’s population growing by more than 6,000 during the same time span.

Is ‘buying the block’ the answer?

The rapid progression of gentrification and subsequent displacement of Black communities has inspired influential Black figures such as Jay-Z and the late Nipsey Hussle to ‘buy the block.’

Black investors across the country have started buying property in Black neighborhoods to help curb gentrification. However, some experts believe that “buy the block” movements aren’t enough to lift neighborhoods out of poverty.

In the book Whiteness of Wealth, Emory University Professor Dorothy Brown claims that the benefits of homeownership are not evenly distributed between Black and white homeowners.

She notes that “When neighborhoods remain predominantly Black, the housing stock has lower value.” Even when they buy their homes, Black communities are still subject to the dangers of gentrification.

Government efforts that incentivize private investment, such as Opportunity Zones (a federal program rewarding developers who invest in poor areas with generous tax cuts), don’t necessarily have a mass effect on poor Black communities.

Although private investment is critical to improving disinvested neighborhoods, it always comes with the risk that most of the wealth accumulates with those who already have it.

A recent study conducted by the University of California Berkeley confirmed that the Opportunity Zones program has failed to stimulate meaningful investments in poor neighborhoods. Additionally, most of the tax benefits have gone to areas that were likely to have improved without the need for a tax break.

If not private investment, what mechanisms can strengthen rates of Black homeownership in NYC?

Vivian Tejada is a freelance real estate writer from Providence, RI. She writes SEO blogs for real estate, travel and hospitality companies. She's passionate about the future of work and helping Latin American freelancers achieve time, location, and financial freedom. When she’s not writing you can find her at the gym, a family cookout, or at brunch with her girls. Follow her on Linkedin to learn more.