Redlining was a discriminatory housing practice popularized in the 1930s in response to housing shortages across the United States. While officially banned in 1968, the effects of inequity stemming from redlining continue to haunt American cities, with redlined neighborhoods experiencing worse living conditions than green neighborhoods.

Within New York, redlining condemned dozens of Manhattan and Brooklyn neighborhoods as hazardous and unworthy of investment, shaping New York’s infrastructure from the 1930s up until today. The long-term effects of redlining persist in multiple ways, from continual income inequality to infrastructural decay; previously redlined areas experience higher levels of pollution than their counterparts.

What is Redlining?

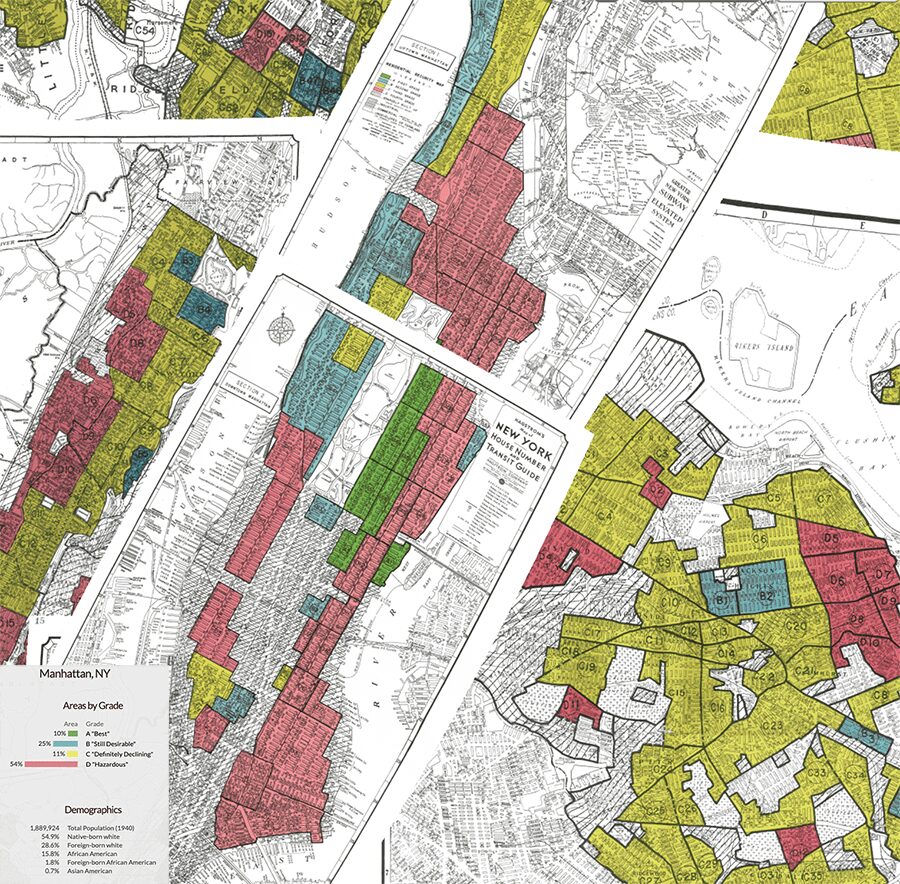

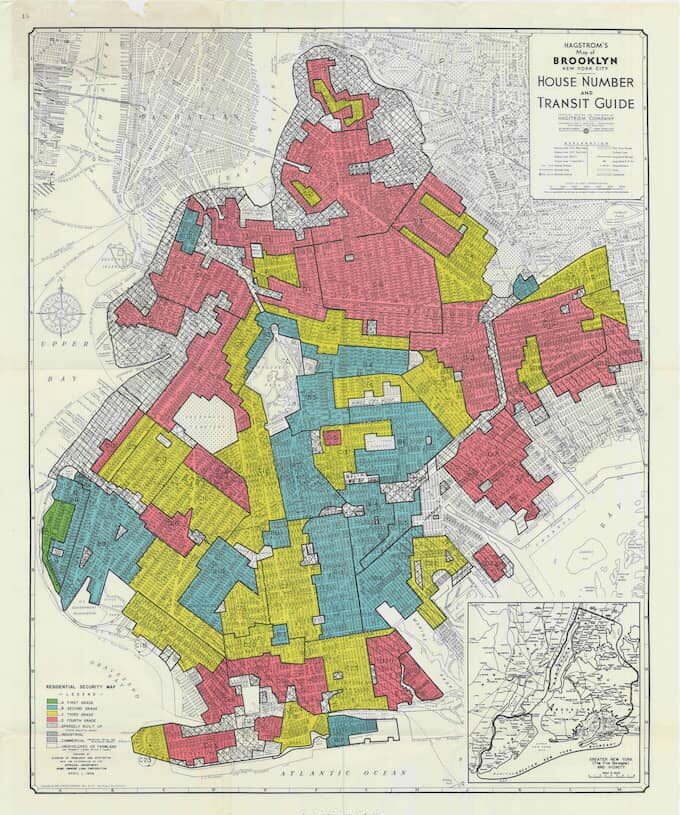

Redlining evolved from the color coding of city maps. During the 1930s, the government-run Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) created “Residential Security” maps of all major American cities. These maps were color-coded to measure risk and potential profitability, informing builders, lenders, and appraisers on areas worthy of investment. These maps became a blueprint for future suburban development while also leading to decades of racial discrimination.

Areas colored green indicated a “Best” neighborhood, while yellow and red coloring meant “Declining” to “Hazardous.” Neighborhoods considered high risk were “redlined” not only on maps but also by lending institutions. Houses in redlined communities suffered exclusion and were blocked by government lending programs. Purchasing a home within redlined communities disqualified buyers from government-secured loans and insurance programs. This disproportionately impacted people of color (POC), mainly Black and Hispanic communities, and led to mass segregation of American communities.

Redlining is synonymous with the systemic denial of financial services, such as mortgages, insurance, and loans, based on geographic location rather than on the individual. But how was this practice ever legal to begin with? It was actually created and promoted by the Federal Housing Administration.

The Dark History of Redlining

The United States government is now considered one of the main segregators of modern-day America. During the housing shortage of the 1930s, the US government made efforts to restructure the layout of American housing. Under the New Deal, housing programs were created to offer affordable housing to white middle-class and lower-middle-class families.

Minorities and families of color were left out of these programs and pushed into urban housing projects. In 1934 the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) was created to oversee mass housing construction. The FHA subsidized builders creating housing subdivisions for white people, even issuing a requirement that none of the homes could be sold to Black people. At the same time, the FHA refused to insure mortgages in or around Black neighborhoods. On top of that, any neighborhood that contained Black residents was automatically redlined. In essence, redlining made it legal to deny Black people home loans while also relegating minority neighborhoods to disrepair.

Author Richard Rothstein ties our current sociological issues back to these racially motivated policies and actions. “The segregation of our metropolitan areas today leads … to stagnant inequality because families are much less able to be upwardly mobile when they’re living in segregated neighborhoods where opportunity is absent,” he says. “If we want greater equality in this society, if we want a lowering of the hostility between police and young African-American men, we need to take steps to desegregate.”

From a current standpoint, it’s easy to see neighborhoods were redlined on baseless claims. It was argued that if minorities purchased homes in majority-white suburbs, property values would go down, placing insured homes at risk. Once the Fair Housing Act was passed, it became evident that property values actually rose when POC families bought in white neighborhoods. Due to restrictive housing with limited options, those families were willing to pay more for housing, causing property values in the area to rise. The only problem is Black people couldn’t secure housing loans.

The ways in which redlining was written into work manuals are shocking to some. The FHA first published its Underwriting Manual in 1938, which stated that “incompatible racial groups should not be permitted to live in the same communities.” In populous cities such as Detroit, builders were not allowed to construct housing developments near Black communities unless a 6-foot-high cement wall was erected to separate the two developments.

Another recommendation outlined in the Underwriting Manual was to separate Black neighborhoods from white by constructing a highway between the two. From looking at the maps, you can see many redlined neighborhoods in Manhattan are in place next to highways.

These walls and highways became emblematic of American segregation and racial discrimination, forcing communities of color into polluted, struggling areas.

The practice of redlining was finally overthrown during the Civil Rights movement, officially banned by the Fair Housing Act of 1968. The act was signed by President Lyndon B. Johnson in the wake of the Martin Luther King assassination riots. Prohibiting discrimination concerning the sale, rental, and financing of housing based on race, religion, national origin, or sex, the Fair Housing Act made individual acts of discrimination illegal in housing transactions. This would allow mobility between race and neighborhood, opening doors for people of color and Black families to live in whatever area they would like. Unfortunately, it was not quite that easy. While residential segregation by race began to decline after the act passed, the promise to promote further integration was never truly realized, and much tension persists today. Studies have found that over a hundred formerly redlined cities remain just as segregated today as they were in the 1940s. The aftereffects of redlining are not set to end anytime soon.

Redlining in New York

The boroughs were no exception to redlining. Demographics and maps from 1940 show the majority of grade A, green-lined neighborhoods were those surrounding Central and Prospect Park, while much of north Brooklyn and eastern Manhattan was redlined due to living conditions, wages, and the presence of immigrants. If a neighborhood contained any Black residents, it was automatically redlined. Chelsea, Hell’s Kitchen, and Lincoln Square were redlined, along with the river-facing portions of Yorkville, the Upper East Side, and Lenox Hill. Harlem and East Harlem, up past Washington Heights, was redlined property. Areas around Harlem still struggle today with worse living conditions than those neighborhoods directly surrounding Central Park.

In 2016 a team of scholars published a project called Mapping Inequality, publishing both color grades and detailed notes from the redlined maps. Grade A areas of Manhattan include the portions of East Harlem, Upper East Side, and Yorkville that bordered Central Park. Further west, Morningside Heights and the Upper West Side were B-graded. Nearly all areas outside of these neighborhoods were redlined. Over the Lower East Side, comments say, “An old district, many ‘old law’ tenements and converted dwellings… Continued obsolescence thru non-conformity with the Multiple Dwelling Law.” An example of neighborhood categorization can be seen in a write-up of 2nd Avenue: “An old tenement district. Rentals largely in the lowest brackets and almost all under $30. Has tendency to improve but not at all active in recent years. Some modernization. Large development on York Ave. reflected in trend. Foreign-born families: 45% Czech Austria predominating. Negro: No.”

Much of northern Brooklyn was redlined: from Greenpoint to Crown Heights and over to East New York. Carroll Gardens, Gowanus, and land surrounding the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Grade B blue-lined portions include Prospect Park South down to Sheepshead Bay, Lefferts Gardens, and parts of Park Slope and Prospect Heights, which directly bordered Prospect Park. A small portion of Bay Ridge is color-coded green.

Other areas of the city, such as Queens, have even fewer green areas. Flushing and Corona were redlined, while most areas surrounding the East River are yellow, exceptions being Bayside, Whiteside, and Douglaston Little Neck. Neighborhoods surrounding the current John F Kennedy airport were redlined, with much of the remaining Queens marked yellow.

Much of this legacy carries on today, as neighborhoods surrounding Prospect Park and Central Park remain unaffordable to many. Many redlined neighborhoods still exhibit difficult living conditions. Until recently, much of Brooklyn’s Williamsburg and Bedford-Stuyvesant were working-class neighborhoods considered undesirable for housing purposes.

Pollution and Inequality Amongst Redlining

Recent studies find direct correlations between redlining and neighborhood pollution levels. Communities of color are often exposed to higher levels of air pollution, at great risk to their health. A team of experts found that in 202 cities, modern pollution levels directly correlate with the color grading system established by the New Deal.

Despite improvements in air quality around the US, levels remain high within Black and Hispanic neighborhoods. Minority and Black neighborhoods are often near emissions infrastructure, including roads, ports, rail lines, and industrial facilities. Redlined areas were determined by the presence of Black or immigrant communities and proximity to pollution sources. While the majority of rail lines were laid prior to 1930, most highways were constructed after the 1930s and were preferentially constructed through Black and brown communities as mandated by the FHA.

One example is Flint, Michigan. Redlined in 1937, Flint was considered one of the most segregated non-southern cities in the United States. Today, residents battle for access to clean drinking water after tens of thousands were exposed to harmful levels of lead, leading to an outbreak of Legionnaire’s disease. Government officials downplayed the outcry until residents began to protest. Five years later, sanitary drinking water has not been restored.

Income levels also vary in tandem with grading scales. In 64% of grade D neighborhoods, the population is a majority of people of color. Within 74% of grade D neighborhoods, the income level remains low to moderate.

These discriminatory practices have had lasting effects and still resonate with living styles today. The lines of segregation remain constant in most cities, and New York shows similar demographic breakdowns today as it did fifty years ago. A study by FiveThirtyEight found that, out of 138 cities, almost all formerly redlined areas were still majority Black, Latino, or Asian, while two-thirds of the greenlined neighborhoods are still majority white. The numbers have not shifted significantly.

“The redlining maps are like the Rosetta stone of American cities,” says LaDale Winling, professor of history at Virginia Tech and a researcher for the Mapping Inequality project. Redlined zones in the Northeast and Midwest are found to be the most segregated within the country. While it’s hard to imagine what this country could look like had it not been for redlining, our cultural history has so seeped in racial tension that it’s impossible to imagine an American without segregation. Hopefully, with careful analysis of the past and help from forward thinkers, New York, and other large and small cities can move into a more harmonious future.

Lindsey Rae is a freelance writer, videographer, and medium format photographer with a background in economics, documentary filmmaking, and human rights. In past lives she covered the arts scene in Seattle and LA before morphing into a finance journalist, reporting from the NYSE for German news media. When not writing about culture & lifestyle she can be found studying herbalism and traditional healing techniques. She enjoys running, yoga, and world travel. You can find her at www.linerae.com or IG @hunteressthompson