It’s a beautiful day in SoHo: the sun peeks through stately cast iron buildings to shine down on cobblestone streets teeming with residents, business folk, shoppers, Instagrammers, and tourists. Beyond its designation as a bustling shopping and dining district, SoHo exists as a very significant architectural and historical piece of New York City history. The neighborhood boasts the largest collection of cast-iron buildings in the world, with approximately 250 structures. Built from the mid-to late-1800s, these buildings have quite literally stood the test of time and modernization… mostly in part, thanks to the actions and activism of one woman.

This is the story of Margot Gayle.

Who Was Margot Gayle

Born in 1908 in Kansas City, MO, Margot spent much of her childhood moving around due to her father’s job as an executive in the auto industry. Gayle didn’t grow up wanting to be a historical preservationist; she actually received a Masters in bacteriology from Emory University, but the Great Depression made it difficult to find a job. So she turned to politics and became an activist through her work. One of her early accomplishments was fighting to get the Georgia poll tax repealed. She was so passionate about the cause that many dubbed her “Poll Tax Margot.”

Gayle moved to New York with her husband (divorced in 1957) and two daughters, where they lived in Greenwich Village. In New York, she continued to be involved in political activism, even running for City Council in 1957. It was through her work in politics, however, that she found her true calling: historical preservation.

Jefferson Market Courthouse

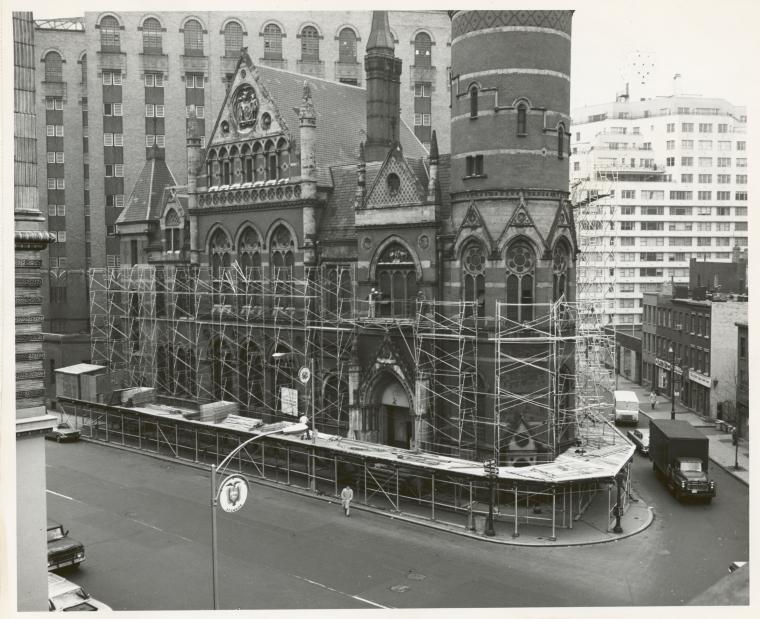

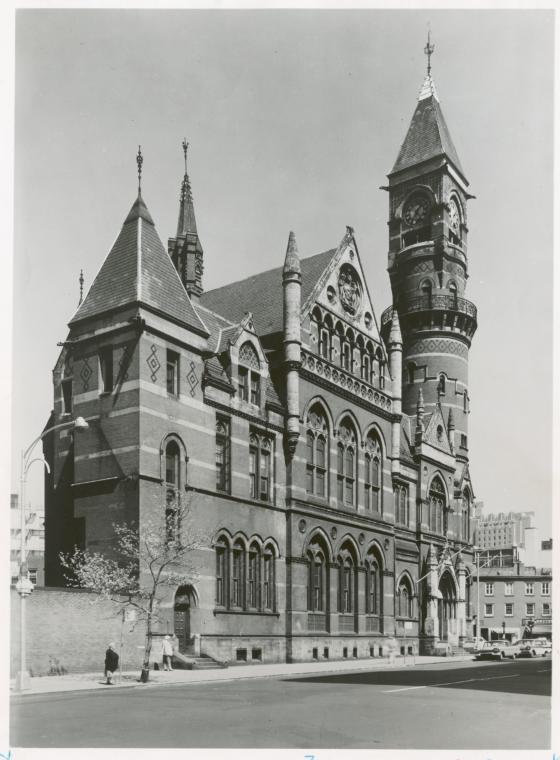

Located at 425 Avenue of the Americas, the Jefferson Market Courthouse – an iconic Victorian Gothic structure built in the late 1800s – was around the corner from Margot Gayle’s Greenwich Village apartment and from the notorious New York Women’s House of Detention. One of the most defining characteristics of the red brick structure was its spire-like clock tower. It was used as a courthouse until 1945, after which it sat vacant, the future of the historic building uncertain. In the late 1950s, rumors that the courthouse was for sale and in danger of being torn down prompted Margot Gayle to take action.

With the help of friends and colleagues, Gayle formed the Village Neighborhood Committee. One of the organization’s first orders of business was to get the long-frozen clock ticking again, with the hope that it would raise awareness. It did just that. Next, the committee set out to ensure that the building itself could be preseved. A successful campaign to have the former courthouse converted into a public library sealed the deal. In 1961, the New York Public Library agreed to take over the structure, and in 1977 it was declared a National Historic Landmark.

Reflecting on her work saving the Jefferson Market Courthouse, Gayle said in an interview with the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation, “It was ‘act soon or lose it.’ There was no precedent for what we were doing, and there was very little community feeling about saving old buildings, so we couldn’t really use that. We just used every tool at hand and worked fast to keep the building from being auctioned off, really. I really am amazed to think how close that building came to being gone.”

The Jefferson Market Library is in full operation today.

Formation of the Victorian Society

The Jefferson Market Courthouse may have been Margot Gayle’s first big win, but it was hardly her last. In the 1950s and 60s in New York, the demolition of historic masterpieces to make way for modernization was plaguing the city. It was activists who saved some of NYC’s most iconic NYC fixtures – notably, Jane Jacobs’ successful 1958 battle to stop Robert Moses from building a highway through Washington Square Park.

Unfortunately, not all could be saved. In 1963, the original Pennsylvania Station was demolished to make way for Madison Square Garden. Renowned for its beauty, the original structure was considered “the architectural embodiment of New York’s vaulted ambition and open arms.” Its demolition was devastating to residents.

More on CitySignal:

Determined to ensure other historic cast-iron structures would not meet the same fate as Penn Station, in 1966, Gayle, in conjunction with historic preservationists Brendan Gill and Henry-Russell Hitchcock, founded the Victorian Society in America. Still in existence today, the Victorian Society is committed to “historic preservation, protection, understanding, education, and enjoyment of our nineteenth-century heritage.” The organization fulfills its promise through architectural tours, publications, and summer schools dedicated to educating interested parties on architecture, art, and preservation.

Friends of Cast Iron Architecture

The Victorian Society was not the only preservation organization that Margot Gayle helped create. In 1968, she attended a Victorian Society symposium during which she learned about the significance of cast iron buildings in New York and that they were largely unprotected. Inspired and enraged, Gayle made it her mission to fight for their survival.

On March 18th, 1970, Gayle formed the Friends of Cast-Iron Architecture. The group’s goal was to “preserve structures such as cast-iron buildings, cemetery ironwork, and iron fountains – both nationally and internationally.” By raising awareness about the significance of cast-iron architecture in America, the organization has successfully prevented the majority of cast-iron structures from being demolished. It was through the Friends of Cast-Iron Architecture that Gayle was able to fight out one of her most consequential and important preservation battles.

SoHo Cast-Iron District

In the late 60s and early 70s, urban renewal in New York was the name of the game, and SoHo was under imminent threat. In 1969, the area faced the danger of demolition to make way for the LOMEX – Lower Manhattan Expressway – an elevated highway that would connect the Hudson to the East River. Thanks to outcry from residents, artists, and activists like Gayle, the project was halted permanently in 1969.

Though the area was safe from an expressway, preservationists craved security to ensure the neighborhood would also be spared from modernization. Over the next few years, Gayle and the Friends of Cast-Iron Architecture worked tirelessly to get the area designated as the SoHo Cast-Iron District. Her partners in crime were the artists who called the area both home and work (the “SoHo model” has gone on to serve as an example for mixed-use artist spaces). Their joint efforts paid off in 1973, when SoHo received a Cast-Iron District designation from the Landmarks Preservation Commission, thereby protecting the historic architecture from demolition.

Today, with rents higher than the buildings themselves (average rent for a one-bedroom is 4,650 according to RentHop), SoHo is hardly a haven for artists looking for a studio to work and live in. It has transformed into a glamorous shopping, eating, and working destination – likely in part, due to the district’s unique architecture. Much like the Jefferson Market Courthouse, by preserving the bones of the buildings, SoHo had the chance to change with the times while holding onto its history. And that is thanks to Margot Gayle.

Ms. Gayle died in 2008, but her work will be remembered forever. On her passion for preservation, she once said: “If one person really puts his mind to something and can inspire a whole group around him, it’s amazing in this complicated world what can be achieved. How do you like that?”

We like it very much, Margot.

Emily Bice is a New York based writer born in Michigan, but with family in Canada - so on paper she’s the nicest person you’ll ever meet. Emily graduated from The University of Michigan’s School of Music, Theatre, and Dance. She has worked as an olive oil farmer, press correspondent at Cannes, and in television, but her favorite job is writer. Playwriting credits include before the flood (The Chain Theatre, NYC), Purgatory (developmental workshop, Ann Arbor, MI), See You In A Few (one act, the thing theatre company, Zoom). Check out more of her work at emilyabice.com!