During construction, the building was so beautiful people would ask the security guards how to get an apartment there. The guards would respond jokingly, “Kill your husband.” Residents and tourists had no idea the 11-story art deco façade would eventually hold hundreds of female inmates. While in operation, the controversial House of D imprisoned notable women such as Angela Davis, Valerie Solanas, Mae West, and Afeni Shakur.

Nowadays, few would guess the lush and bountiful garden beside the Jefferson Market Library was once a notorious women’s jail. Walking through the upbeat and upscale Greenwich Village today, it is quintessential New York in all its splendor; a neighborhood with brownstones, delis, subways, and iconic tourist destinations like NYU, the New School, and Washington Square Park. Yet, for some, history cannot be erased. For members of the queer community, the New York Women’s House of Detention (House of D) existed as a painful reminder of intolerance and government-sponsored abuse. The prison would leave its mark on Greenwich Village and New York in many ways.

The prison’s eventual closure was celebrated by even the mayor, who spearheaded the demolition committee and took an honorary first jab at destroying the building. This probably came as a surprise to the designers of the prison, who viewed it as ahead of its time, the beginning of a new path in incarceration. “It is the first of its kind in the country and may serve for the guidance of other communities,” said an anticipatory 1931 New York Times article. How did it come to fall so short?

The First and Only Art Deco Prison

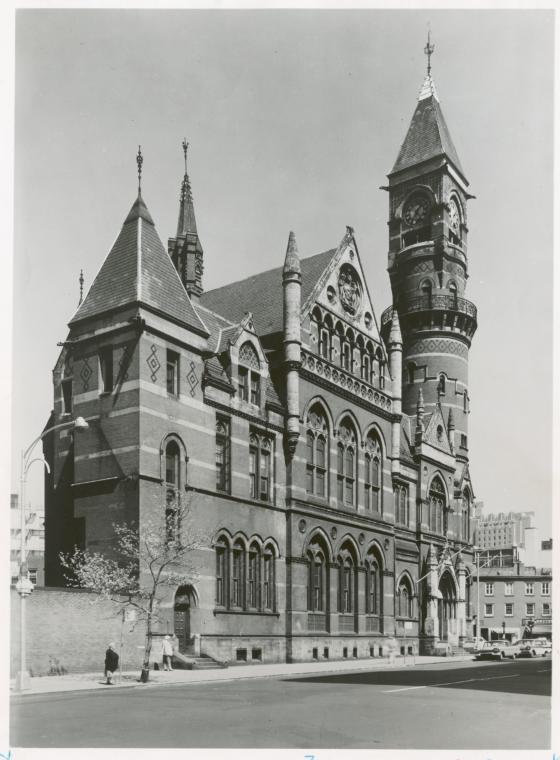

Built in 1931, the New York Women’s House of Detention was the only women’s prison to exist in Manhattan. Often called the House of D, it was designed by Sloan and Robertson and constructed for $2 million. The prison was built on the site of the Jefferson Market Prison, located at 10 Greenwich Avenue in the heart of downtown Manhattan. Inmates began to arrive as soon as 1932, and it quickly filled beyond capacity.

The prison was controversial throughout the entirety of its operation. Called the “world’s only art deco prison,” the House of D inspired protest and criticism alike due to harsh treatment of inmates and severe overcrowding.

Through The House of D Formed Community

Historian Hugh Ryan researched the prison extensively for his book The Women’s House of Detention, noting, “It was one of the Village’s most famous landmarks: a meeting place for locals and a must-see site for adventurous tourists. And for tens of thousands of arrested women and transmasculine people from every corner of the city, the House of D was a nexus, drawing the threads of their lives together in its dark and fearsome cells.” Over the decades, a number of independent events solidified the Women’s House of Detention as an important part of American and LGBTQ+ history and culture.

Many famous women were incarcerated throughout the years, including author Polly Adler, far-left radical Jane Alpert, political activist, and philosopher Angela Davis, journalist and anarchist Dorothy Day, Black Panther and activist Afeni Shakur, Broadway film actress Mae West, author and activist Grace Paley, and radical feminist Valerie Solanas, who shot Andy Warhol.

The House of D played a pivotal role in the LGBTQ+ community, establishing Greenwich Village as the gay capital of New York. When gay bars and drag shows were being raided in the 1950s, arrested women- queer women and trans men- were brought to the House of D. By default, it became a congregating place for queer and trans folk navigating the penal system. Greenwich Village, by extension, grew into a de facto hub for New York’s queer and trans population.

The Women’s House of Detention was also a prolific space during the gay rights movement of the 1960s and the Stonewall Uprising of 1969. The House of D’s close proximity to Stonewall Inn, less than 500 feet, meant prisoners were able to watch the riots from their windows. Eventually, rioting broke out among prisoners, and many set fire to their belongings, chanting, “Gay rights! Gay rights!”

House of Detention And Proper Women

The first superintendent of the prison, Ruth E. Collins, called the Women’s House of Detention a “new era in penology.” She commissioned artworks and murals to be placed on the grounds to uplift inmates. She believed in redemption.

A notable feature of the prison was its intention to rehabilitate women back into society as “proper women.” Women could move upwards and out of poverty through two main avenues: being a wife or being a maid. Queerness, it was thought, hindered women from integrating properly into society.

Ryan notes that the treatment of women was appalling compared to the treatment of men in men’s prisons, “Things that weren’t considered crimes or were considered something you would get a fine for or a citation suddenly become vectors for incarceration when applied to Black people and to women.”

Many prisoners were incarcerated through crimes dealing with gender-nonconforming behaviors. In essence, being the “wrong” kind of woman could get anyone a stay in the House of D. “Waywardism, disobedience to their parents, being out at night by themselves,” were all things that could get a woman arrested, says Hugh Ryan, “wearing pants, accepting a date from a man, accepting a ride from a man.” A woman seen as improperly feminine or too masculine could be incarcerated for waywardism by her parents or a stranger.

Allegations began to arise of racial discrimination, abuse, and mistreatment. By the 1960s, it was estimated around 75% of incarcerated individuals were queer. The prison was exceptionally hard on its queer population, marking gay prisoners with a “D” for degenerate and subsequently placing them into solitary confinement for being a danger to the other women. New prisoners underwent a harsh pelvic and physical exam during their entry.

The building was under constant scrutiny from residents, investigators, and picketers. During its final years, the prison was a focal point for frequent protests by groups calling attention to the repression of women, homosexuals, and minorities.

Investigators and journalists began sharing stories from inside the prison. Inmates detailed horrendous living conditions, including rats, mice, flying bugs and inadequate medical care, unpalatable food, and inmate-staff intimacy. Some inmates displayed to reporters the bites they got from insects in jail. Assemblyman Kottler found the House of D was a “hellhole” that made him “physically sick.” Overcrowding was a major issue. The original building capacity was set to 457 people, but the prison often held more than 750 inmates.

The Downfall of the House of D

Before the prison was fully operational, the New York Times said it “looks not unlike a better-class apartment house. Taxpayers who feared that the new jail would have a depressing influence on land prices in the neighborhood welcomed it as an asset once it was built.”

That sentiment did not last for long. Passerbys and local residents could not escape the prison; inmates would shout from the windows at all hours of the day. Prisoners often pressed themselves against bars to talk with people and friends passing by. This led locals to believe it was “the wrong building in the wrong place.”

The pivotal downfall for the House of D came when 18-year-old Andrea Dworkin was arrested for protesting the Vietnam War in 1965. During intake, two doctors forced a pelvic exam on her.

Middle class and white, her family was well-connected. Upon release, Dworkin told reporters about the violent and dehumanizing assault. She received coverage in the New York Post by James Wechsler, a widely read columnist, leading to multiple investigations into the prison. His column was a harsh rebuke, “The truth is that the Women’s House is an unfit habitation for any human soul. A sweeping exploration of this case might finally hasten its end.” City and state government officials took note, launching multiple investigations into facility operations.

Andrea Dworkin’s testimony was the first move in its eventual closing. “The move to get rid of the House of D and move women over to Rikers basically starts in that moment,” said Hugh Ryan.

The prison officially closed in June of 1971. That month 422 inmates were loaded on buses and transferred to a new facility on Rikers Island as part of a new correctional center dedicated to Mayor Lindsay.

One correctional officer commented on the change, “No more overcrowding. A chance for the girls to live like human beings.” A local resident remarked, “At long last no more raucous, bawdy exchanges.”

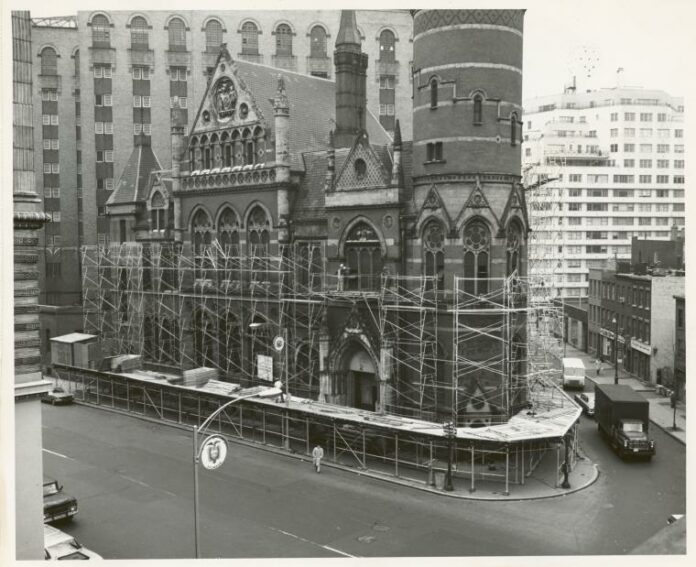

Calling it a “miserable old dungeon,” Mayor Lindsay initiated the demolition himself, posing for photographs with a sledgehammer and crowbar before climbing the prison scaffolding to take a swing at the granite and brownstone. Onlookers cheered. The mayor then announced that after the razing, the city would make a park on the site.

Finally Laid to Rest

The prison officially closed on June 13, 1971. Mayor Lindsey began prison demolition that was completed sometime in 1974. The prison was replaced with the Jefferson Market Garden. The Jefferson Market Library, standing beside the old prison grounds, offers a studious and quaint respite to the hustle of the Greenwich neighborhood. With a lush garden outside, visitors can read and dream in ways the women of this prison could not.

Lindsey Rae is a freelance writer, videographer, and medium format photographer with a background in economics, documentary filmmaking, and human rights. In past lives she covered the arts scene in Seattle and LA before morphing into a finance journalist, reporting from the NYSE for German news media. When not writing about culture & lifestyle she can be found studying herbalism and traditional healing techniques. She enjoys running, yoga, and world travel. You can find her at www.linerae.com or IG @hunteressthompson