New York City, 1904. It was the year the first underground line in the subway system opened for business, Times Square got its official name, and a hotel located between West 73rd and 74th Street on what would eventually become the Upper West Side, opened with a full-fledged farm on its roof.

The hotel in question was The Ansonia, and it was intended to be the largest and grandest hotel that New York City had ever seen. At the time of its opening, it featured amenities unheard of for a hotel – namely, the aforementioned farm in the sky. But that’s getting ahead of the story.

The Ansonia Opens For Business

The Ansonia was conceived by William Earl Dodge Stokes, a well-to-do New Yorker born into the Phelps Dodge mining operation. Stokes had established himself as a real estate developer in the mid-1880s, buying up and building row houses in the West 70s and 80s. He is largely credited with transforming the Upper West Side from an underdeveloped no man’s land into a residential hub. Two of his early developments still stand today – the Queen Anne-style townhouses at 231-233 West 74th Street, right around the corner from The Level Club.

Though important to the history of the neighborhood, the row houses were only Stokes’ entrance into real estate development; The Ansonia was his magnum opus. Named after his grandfather, industrialist Anson Greene Phelps, Stokes designed the hotel to be a “self-sustaining utopia.” His vision was to create a haven with every amenity under the sun (somewhat literally – one of the most impressive features was a massive domed skylight looming over the grand staircase). At the time of its opening on April 19th, 1904, the 550,000 square foot hotel had a bank, a barbershop, the world’s largest swimming pool, Turkish baths, restaurants, full-service kitchens on each of its seventeen floors, libraries, smoking parlors, ballrooms, an in-house art curator, and, of course, a rooftop farm.

The farm boasted roughly 500 chickens, many ducks, goats, and even a small bear. Stokes’ intention was for guests to get fresh eggs delivered to their door daily, and for three years, that dream was a reality. In 1907, however, the Department of Health caught on and promptly shut the operation down. The animals were sent away, and The Ansonia was farm free… mostly. Stokes’ second wife Helen Elwood cited the 47 chickens which Stokes kept in their family apartment as one of the reasons for the dissolution of their marriage in 1915. Chickens’ legacy in New York City lived on as they are the only farm animals that are not illegal to own in the city.

Though perhaps the most unorthodox, the chickens were not the only notable guests at The Ansonia in the early days.

Checking In To The Ansonia

One of the earliest residents was Al Adams, the New York numbers racket’s millionaire “Policy King.” Adams went straight from Sing Sing to the then two-years-old hotel. He took refuge in The Ansonia for two years, right up until he was found dead in Suite 1579. Though the coroner ruled the passing a suicide, there was speculation that Stokes shot the guest over a gambling debt.

Years after the death of Al Adams, players of a different kind of game checked into The Ansonia: pro-athletes. Heavyweight champ Jack Dempsey stayed while training for his 1919 match against Jess Williard. He was followed by several members of the New York Yankees… including Babe Ruth. Ruth and his wife moved into the hotel after the 1919 season, and it’s said that he felt so comfortable in his new abode he’d often head to his morning shave in the basement barbershop wearing only his silk bathrobe.

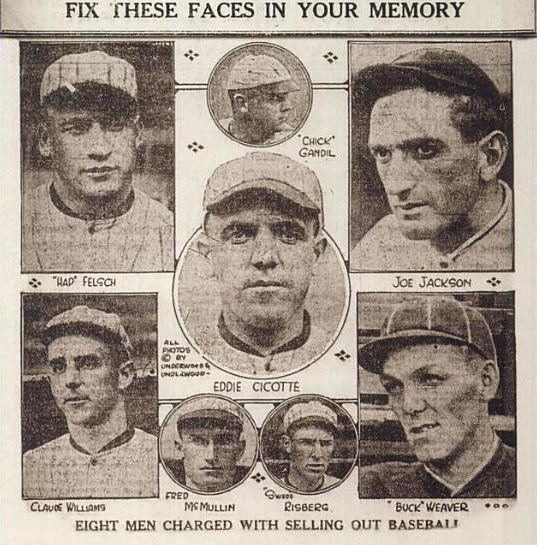

The Ansonia felt like a safe space to many, including members of the Chicago White Sox. On September 21st, 1919, a clandestine meeting took place in first baseman Chick Gandil’s hotel room. The eight-team members in attendance were later accused of fixing the 1919 World Series. After an investigation from a grand jury in 1920, the ‘Black Sox’ were acquitted but banned for life from Major League Baseball. The players’ names will forever be tied to the scandal and The Ansonia, the hotel where it all began.

The Ansonia was also a haven for creative types. Dozens of opera stars took up residence in the hotel, including legendary composer Igor Stravinsky, who stayed from 1926 until the mid-fifties.

Giulio Gatti-Casazza, the general manager of the Metropolitan Opera from 1908 – 1935, also lived at The Ansonia for a time. Gatti-Casazza was hailed as “the Ziegfeld of Opera,” which is interesting, as the legendary impresario Florenz Ziegfeld was also a resident of the hotel.

A Change in Management

A hotel is only as good as its manager, and Stokes – despite his turbulent personal life – cared deeply for the building. Though disappointing, it’s not surprising that things went downhill after he was no longer in charge. William Earl Dodge Stokes died in 1926, but by then the hotel had already been passed to his son, Weddie.

Whether it was Weddie or just bad timing, difficult days followed. Three years after the elder Stokes’ death, the Great Depression rocked the United States, and the roaring twenties screeched to a halt. The well of wealth dried up, and that’s never good news for a luxury hotel. All restaurants, kitchens, and guest rooms were closed; only rental units were left. With the escalation of the Second World War came a domestic effort that meant contributing as much as possible to the fight overseas – for example, making bullets and tanks out of the melted-down copper cartouches from The Ansonia’s once-magnificent exterior. The grand entrance was bricked over to make room for storefronts, and the awe-inspiring skylight was covered up.

Weddie sold the hotel to corrupt landlord Samuel Broxmeyer in 1945. Broxmeyer had no interest in the legacy of the hotel – he only wanted to make a buck and didn’t care how. Broxmeyer received five years in jail for his crooked practices, and the hotel was sold at a bankruptcy auction for $40,000 to Broadway Sign manufacturer Jacob Starr.

Starr inherited a dying hotel. Nothing was up to code: the pipes were rusted, the roof was leaking, the balconies were falling apart. Since it didn’t exist at the time of building, there was no certificate of occupancy, and so the hotel was effectively housing residents illegally. It was a hotel in decay, and would take millions to repair. So, in 1968, to “cover repair costs,” Starr rented out the Turkish baths to former opera singer Steve Ostrow, who in turn opened the “Continental Baths,” a gay bathhouse.

Ostrow’s dream was not dissimilar to Stokes’ utopian dream for The Ansonia; Ostrow set out to create a safe space for its guests that was “reminiscent of the Roman glory days.” Decked out in Gilded Age decor, the bathhouse actually became most well-known for its musical performances. The shows drew in quite a crowd: audience members included Mick Jagger, Bob Fosse, Alfred Hitchcock, and Andy Warhol.

Bette Midler got her start performing at the Continental in 1970. Already a successful Broadway actress at the time, Midler’s shows at the Continental (accompanied by Barry Manilow) catapulted her into national fame and put the bathhouse on the map as the place to see exciting new acts. She would eventually give a nod to her roots with the album “Bathhouse Betty,” released in 1998. In the most recent season of American Horror Story: NYC, similar scenes of Midler performing are replicated as the bathhouse becomes central to the season’s plot. Perhaps the show’s creators, Murphy and Falchuk pulled examples from the Ansonia to inspire their writing, there is enough scandalous behavior to be used in the series.

All good things come to an end, and the Continental closed in 1976. It reopened as “Plato’s Retreat,” a straight swingers venue, in 1977. Plato’s Retreat did not offer dancing or music; instead, the haunt was known for seedy and often illegal sexual activity. The club was closed on New Year’s Eve in 1985 after the New York City Health Department shut down bathhouses in response to the HIV/AIDs crisis. No new residents have taken up business at the Turkish baths since.

The rental of the baths was intended to “help cover repairs at The Ansonia.” Those fixes did not happen, and in 1968, frustrated tenants decided to take a stand. A change in housing codes made it possible for long-time resident Harry Garland to form the building’s first tenants’ group. With the help of a lawyer, the group took a stand: no rent until repairs.

Starr didn’t like this and decided to demolish The Ansonia as retaliation. But the vindictive landlord underestimated his tenants and their love for the humble haunt; the Ansonia Residents Association appealed to the Landmarks Preservation Commission to designate their home as significant. 25,000 signatures and one star-studded concert on 73rd Street later, they succeeded. The Ansonia became a landmark on March 14th, 1972. Starr was dismayed, and the residents were delighted; their home was safe.

Safe from demolition doesn’t mean safe from change. Starr sold the building to new owners who poured millions into the revitalization of the building before realizing that the best solution would be to go condo. Most of the tenants were bought out when The Ansonia was converted to condominiums in 1990.

Living Large At The Ansonia

The Ansonia was always intended to be a luxurious home for the cream of the crop. In many ways, today it reflects that original vision. Gone are the baths, the restaurants, the baseball players, and the chickens on the roof. Instead, there are million-dollar apartments and celebrities – maybe still some who wear silk robes a la Babe Ruth, though likely not in the elevator down to the basement barbershop.

The Ansonia’s history has also inspired endless stories, including Hulu’s “Only Murders in the Building.” The building is nothing close to what it was when first built in 1904; then again, neither is New York. The landmark has changed with the times. Hopefully, Stokes would be happy to know it still stands tall today.

Emily Bice is a New York based writer born in Michigan, but with family in Canada - so on paper she’s the nicest person you’ll ever meet. Emily graduated from The University of Michigan’s School of Music, Theatre, and Dance. She has worked as an olive oil farmer, press correspondent at Cannes, and in television, but her favorite job is writer. Playwriting credits include before the flood (The Chain Theatre, NYC), Purgatory (developmental workshop, Ann Arbor, MI), See You In A Few (one act, the thing theatre company, Zoom). Check out more of her work at emilyabice.com!