New York City—both fairly and unfairly—has gained a reputation as one of our country’s grungier cities. But even if litter, roaches, and rats remain an issue in today’s New York, the city’s current conditions cannot be compared to the filth and stench endured by New Yorkers before the widespread implementation of indoor plumbing.

Before the Toilet

The modern flush toilet is descended from a model perfected by English plumber Thomas Crapper in the late 19th century, which he based on earlier designs created by inventors Alexander Cumming and Sir John Harington. However, this type of toilet relies on an integrated plumbing system and water pressure to operate, both of which were scarce in New York City until the last 150 years. Even as late as 1940, half of all homes across America did not have hot piped water, a bathtub or shower, or a flushing toilet. Instead, people were forced to deal with much messier and less sanitary options whenever nature called.

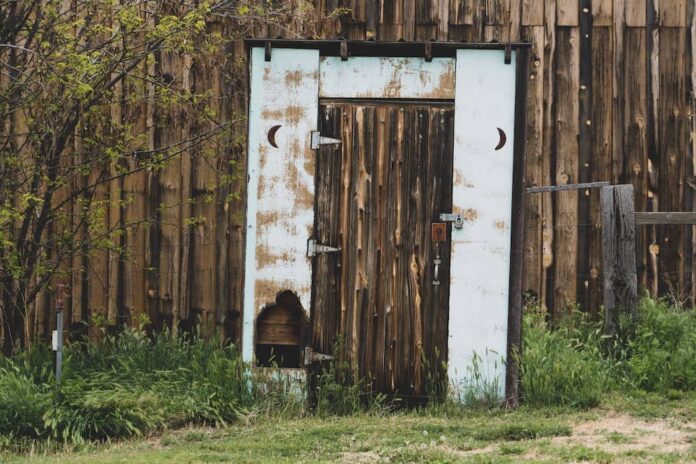

Historically, urban areas faced particularly unique challenges when it came to the disposal of human waste. Outhouses were the most common type of toilet facility available across the country. Chamber pots were another short-term indoor option, though these were generally emptied directly into outhouses to consolidate waste. In rural communities, outhouses consisted of semi-permanent outdoor structures containing a seat suspended over a waste pit. When the waste pit began to overflow with sewage, it was covered with dirt, and a new pit was dug in another location on the property. In cities, however, the lack of available land necessitated that outhouses remain as permanent structures. As such, the waste, which could not be buried, required removal.

Disposing of Waste

“Night soil men” or “nightmen,” so named because their work was carried out long after dark to spare everyday citizens the nauseating stench of human excrement, were thus hired by contractors to empty the city’s outhouses. Being a night soil man was hardly an enviable position, but it was a very lucrative one, as there was virtually no end to the demand for their services: in the year 1844 alone, New Yorkers generated approximately 800,000 cubic feet of waste, and this figure only ballooned further as the city’s population continued to grow over the 19th century.

A night soil man’s job varied a bit from commode to commode. For instance, the emptying of a wealthy family’s private outhouse was a much simpler affair than cleaning out a tenement outhouse shared by several dozen people. Regardless of their customers’ circumstances, most waste was removed using a long-handled bucket to scoop the excrement into a barrel or similar vessel that was then loaded onto a horse cart. The night soil men would drive through the darkened streets to jettison their unpleasant burdens not into a sewage treatment center but directly into the East and Hudson Rivers and even New York Harbor.

Building the Sewer

Unsurprisingly, this disposal method frequently impacted public health across the city, resulting in massive cholera outbreaks in 1832, 1849, and 1866. Mortality rates during these outbreaks could reach as high as 50 deaths per 1,000 people. Epidemics of dysentery, typhus, and typhoid fever were also extremely common. As scientific understanding of disease and sanitation evolved, cities began to regulate the activities of night soil men more strictly and impose fines on anyone caught dumping waste in any public area or body of water. With nowhere left to conveniently offload this excrement, and its existing open-air sewage canals only further contributing to the city’s health crisis, New York City was forced to construct a sewage system to manage its waste flow.

Construction on New York City’s sewer began in earnest in 1849, propelled partly by that year’s spike in cholera cases. By 1855, over seventy miles of sewage channels had been laid throughout the city. The full installation of New York’s sewer took nearly half a century, but most of the city had finally been connected to the sewage system by 1902. Today, there are more than 6,600 miles of sewer pipes in New York City—to help with visualization, that’s double the distance between Times Square and Fairbanks, Alaska.

More on CitySignal:

Establishing Indoor Plumbing

The implementation of this sewage system also coincided with and helped to allow for the introduction of indoor plumbing to the city. In the first two centuries of the city’s existence, a crude series of wooden pipes were used to pump water from the Bronx River; city residents could come to one of the several reservoirs served by this somewhat unreliable system to retrieve their water, or else draw from nearby wells and streams. However, there was no way to pressurize this water to propel it to ground-floor bathrooms, much less fill up a bathtub on the upper floors of a multi-story building. This changed with the construction of the Croton Aqueduct in 1842, which helped to provide running water to select areas in Manhattan.

While this luxury was at first only accessible to very wealthy households, the gradual expansion of the city’s aqueduct system over the following decades greatly improved health conditions across the city and eventually made running water available to the general public. The late 1800s also saw the implementation of the first rooftop water towers, which used gravity to create enough water pressure to service even the tallest buildings. The earliest water tower tanks were created by barrel makers, and modern water towers are still often made of wood to take advantage of improved insulation during the winter.

When Did Indoor Toilets Become Common

Indoor flush toilets became commonplace in New York City in the late 1800s, especially in upper-class households. The greatest push for universal indoor plumbing arrived following the Tenement Act of 1901, which strictly required that all residential buildings include at least one indoor toilet per unit. Though it took several decades for this requirement to be implemented, indoor toilets, at last, became the norm across the city. Around this time, the practice of “stacking” bathrooms—that is, placing each unit’s bathroom directly in the exact same place on each story of the building’s floor plan—became standard in residential architecture to streamline the downward flow of water.

One might imagine that New Yorkers were thrilled to finally do away with the squalor of their outdoor toilets, but the implementation of indoor toilets was a contentious matter at first. Many residents were appalled by the idea of having a permanent area dedicated to defecation within their homes, and superstitions persisted that indoor toilets could release toxic sewage gasses into their houses. Very soon, however, the indoor toilet came to be appreciated for the incredible convenience and sanitary benefits it offered.

Managing Wastewater

With toilets now installed inside more and more homes, the city required a means of purifying the new glut of wastewater to escape the pollution that had historically plagued the city’s waterways with filth. The Metropolitan Sewerage Commission was created in 1904 to assess the state of the city’s sewer system and determine the most effective solution. The city’s first three wastewater treatment plants were established in Brooklyn and Queens during the turn of the century, and eight more plants opened across all five boroughs in the following decades. Between 1945 and 1965, the citywide capacity for sewage treatment rose from 497 million gallons a day to 1,037 million gallons a day.

The passage of the Clean Water Act in 1972 mandated an even higher standard of water treatment throughout the country and led to the creation of several more plants. The last of these were not completed until the 1980s; even as late as 1986, nearly all of the Upper West Side’s untreated sewage flowed directly into the Hudson River. Today, New York City’s fourteen wastewater treatment plans have a combined capacity of 1.3 billion gallons each day.

New York’s sewer system was designed as a combined system, meaning that the rainwater collected in storm drains and wastewater descending from residential buildings are combined into the same system. This was an effective method before the implementation of wastewater treatment facilities when all sewers drained into the rivers and ocean; now, however, the city’s combined system means that each time the sewer overflows during downpours, several thousand gallons of wastewater circumvent treatment centers and are released into the streets and surrounding waterways. This system also requires that even relatively clean rainwater must go through the same intense purifying process used for toilet water, which can put a strain on the system during periods of heavy rainfall.

The evolution of the city’s wastewater and plumbing systems is an ongoing project as the city continues to expand and our understanding of the environmental impact of our waste treatment evolves. We may yet see a time when the issues of our combined system are permanently addressed. For now, however, simply take a moment to be grateful that cartloads of human excrement no longer rattle through the city streets each night.

Sophie McIntosh is a Brooklyn-based writer and dramaturg hailing from Sun Prairie, Wisconsin. Her plays have been produced by Imaginarium Theatre Company, Platform Production Company, and in the Boston Theater Marathon. Check out more of her work at sophiemcintoshwrites.com!