It was not always possible for single women to live safely in NYC. Today, we see women of all walks embracing the freedom to live any lifestyle they desire, and much of society celebrates the empowered feminine—but that was not true 150 years ago. Women of the past were called to work in cities like New York City yet were not guaranteed a safe place to live once they arrived. Religious and paternalistic ideals of that era made it even more difficult, as women were expected to uphold visions of chastity and domesticity, yet were paid such low wages they could only afford to live in tenement housing or shared rooms with male lodgers.

It wasn’t until 1891 that the first all-women building opened in New York, and many still remain today. Let’s take a look at the history of all-female buildings and how this movement, despite initial religious overtones, eventually segued to support female independence and modern-day feminist movements.

Housing Crisis for Single Renters in New York City

Industrial growth in the late 1800’s dramatically changed the American landscape. The history of industrialized New York began in 1835, when the city’s expanding infrastructure and industry attracted an endless stream of immigrants and industrialization. Steamships and steam railroads made it possible for people to travel to and from the city, and advances in manufacturing created demand for more working hands. Suddenly, folks from all over the northeast were departing their families and farmlands in search of opportunities in New York City.

With this influx came social tensions, mainly about where to house these newly arrived single occupants. Before then, people lived and worked with their families, often homesteading for generations on a single piece of land. Even in New York City, housing was still geared toward family living. The increase of single people looking for housing was problematic, both for men and women, but moreso for women. Women needed affordable and safe housing if they hoped to establish themselves, but also felt pressure to uphold social expectations of the time.

Tension Amongst New Yorkers and Single Working Women

Men’s living quarters, or “bachelor flats,” became popular starting in the 1880s and provided housing for working-class men who did not have family to live with. But for women, the only options were to split housing with other women, or in some cases, live with male lodgers. Railroad apartments, with multiple but separate rooms, housed many people in each quarter but were known for their squalid living conditions and poor ventilation. Tenement housing was another option, also providing subpar living conditions.

Working-class women earned lower wages than their male counterparts working as seamstresses, shop girls, and factory workers, yet were expected to supply their own housing. This posed two problems for women of those times as there was insufficient housing for them, and they faced great social adversity. While their “manpower” and labor were needed in factories and industry, they were still expected to nurture and maintain an air of purity and chastity. It was considered immoral for women to be in public unaccompanied and living with men outside of marriage was considered immoral and outrageous. The religious and upper class were critical, and citizens began to fret over the unprotected, unsupervised and vulnerable single working women of New York City.

The Dawn of Moral Homes for Single Women

The women’s housing crisis brought up a paradox that eventually forced a slow but steady change in social norms. An 1879 report from the Association for Inquiry into Conditions of Professional and Business Women counted over 50,000 women looking for work in New York, while “appropriate” accommodation could only house around 500 women.

Religious organizations were already getting in on the action. Starting in 1858, a group of New York women sought to help the situation. Organizing as the Ladies Christian Union (LCU), they bought and converted brownstones into safe and affordable housing for working-class women. According to the Gotham Center for NY History, the homes were run by house matrons known as “mothers,” furnished with basic amenities and offered both breakfast and dinner. Prospective tenants went through a rigorous application process, and once approved, were expected to follow the rules and regulations to maintain their place in the home.

The LCU approved of self-supporting women of strong moral character. Good moral standing and appropriate behavior were expected, along with tidiness, chastity, and punctuality. Tenants had to attend morning prayers, be present for breakfast and dinner and have a bedtime curfew of 10 pm. Monitored visits with guests were allowed in parlor rooms, and women who broke the rules or spoke out against regulations would be told to leave. By the mid-1900’s, the LCU was operating six houses under this model.

The LCU created the initial blueprint for the all-female housing model, inspiring many of the buildings to come. Supporters believed the house rules and discipline were imperative in molding well-behaved future wives and mothers.

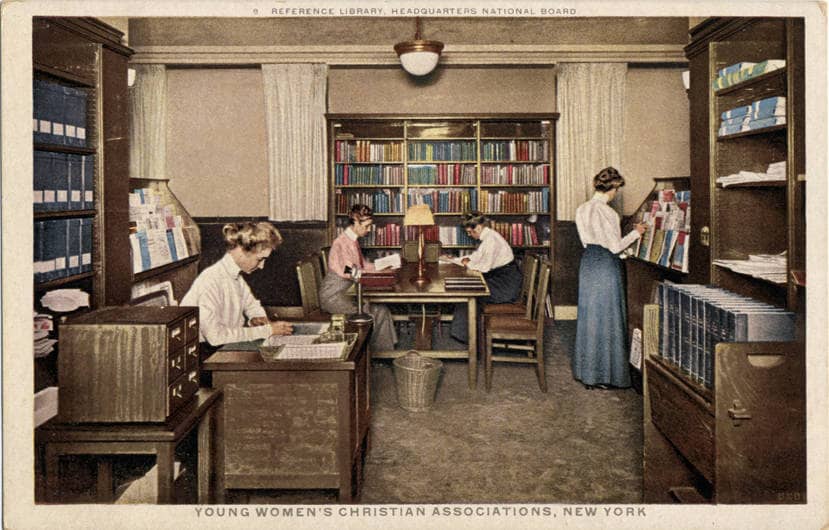

YWCA’s Margaret Louisa Home

Other organizations soon followed suit. In 1891 the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) constructed the 6-story Margaret Louisa Home. Located on 16th Street in Manhattan, this building supported Protestant women of good moral standing. The home was conceived and initiated by Margaret Louisa Vanderbilt Shepard, the daughter of William Vanderbilt, who strongly supported the YWCA and its mission to help women.

Prospective tenants were required to provide evidence of church membership and a mentor’s letter of recommendation. House rules included an 11 pm bedtime, and no cooking or washing was allowed on premises. Other resources were available to help women find their footing, including an in-house employment bureau directing women to open work positions. Tenants could stay up to four weeks, sometimes five, at the rate of .60 cents a night, including both breakfast and dinner.

The home was celebrated as a success in the press. In 1891, The New York Times lauded the Margaret Louisa Home as “certainly a charming place—chaste and really elegant in many of its appointments, and pervaded by an atmosphere of cosy [sic] comfort that is most homelike and satisfying.” While many other buildings were formed with a similar outline, eventually, the housing movement began to support a more independent version of the working woman.

Hotels for Women without Paternalistic or Philanthropic Ideas

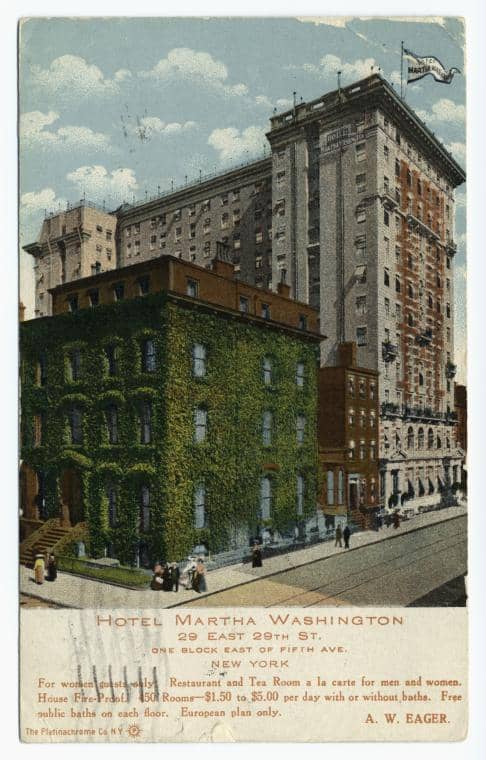

Soon, all-women housing appeared without the religious overtones of organizations like the YWCA or LCU. One example is the Hotel Martha Washington. Opened in 1903 on East 30th Street, this hotel became the headquarters for the Interurban Women’s Suffrage Council in 1907. With a female-only staff, tenants of this building were not required to show church membership or commit to prayer activities. Backed by investors like John D. Rockefeller and Olivia Sage, wife of Russell Sage and founder of Russell Sage Foundation, this 12-story building had 416 rooms, including sewing, laundry, and drying rooms. Also included were a drug store, tailor shop, millinery, manicurist, and newspaper stand.

Rent was $4.50 to $5 a week, including breakfast and dinner. Noted as being “free from paternalism and philanthropic idea,” this hotel operated outside of moralistic ideals and allowed women a taste of independence that was previously unknown. Promotional materials describe the Martha Washington as a “world-famous and interesting hostelry… woman’s wit has been used to provide the little necessities and comforts so much appreciated by her.”

Another notable dwelling was the Barbizon Hotel for Women, located on 63rd and Lexington. Built for the modern woman, considered both “dainty but strong,” this hotel supported business and professional women and was fully booked before its completion in 1928, with over 200 women on the waiting list. The Barbizon Hotel supported women working in the arts by providing artist studios, music rooms, and space for cultural events and exhibitions. Elegant shops lined the ground floor, backed by facilities like dining, reading, and exercise rooms.

Through hotels such as these, women could finally think and live as they wanted to, without the pressure and watchful eyes of so-called “mothers” or religious purists.

The End of Women-Only Housing

Unfortunately, the exploration of women-only housing came to an abrupt halt in the late 1920s. The stock market crash of 1929 and the Great Depression ended the construction on women’s only hotels in New York City. It wasn’t until after the Second World War that construction resumed, this time focusing on housing for nuclear families. Many of the women’s only hotels and buildings continued operation through the 1970s, but most were soon converted to regular, family-style housing. The Webster Apartments opened in 1923 and remain one of the only women’s residences still open for operation.

Modern Day Issues for Single Women Tenants

Women today have more independence and control over their living conditions yet still face difficulties finding safe and affordable housing in a sprawling metropolis like New York City. Tiffiny C, a former New York City resident, musician, and composer, discussed the challenges she faced while renting as a single woman. “The gender pay gap issue directly impacts housing, and women, on average, still get paid less than men. Women also want more security and to live in a unit on a higher floor to feel safer. The area around their home and where they walk matters too. But buildings with added security are more expensive.”

Many women find it difficult to secure an apartment in the first place. “Since I only had one source of income, my application was declined multiple times in favor of couples. I made well over the salary requirements for all of the places I applied, but I was likely seen as a higher risk,” says Tiffiny in an interview with CitySignal. “My credit score was just below 700 at the time, and many landlords would not even consider me, despite providing excellent landlord references and proof of my 100% on-time rent payment history for the last 15 years.”

This story is not new, and many women face the same challenges that their counterparts faced 150 years ago while trying to build their life in New York. Safe and affordable housing is not guaranteed and the obstacles presented are enough to drive many away after only a few years. If only the Hotel Martha Washington could open again today.

Lindsey Rae is a freelance writer, videographer, and medium format photographer with a background in economics, documentary filmmaking, and human rights. In past lives she covered the arts scene in Seattle and LA before morphing into a finance journalist, reporting from the NYSE for German news media. When not writing about culture & lifestyle she can be found studying herbalism and traditional healing techniques. She enjoys running, yoga, and world travel. You can find her at www.linerae.com or IG @hunteressthompson