The following article may contain graphic imagery related to suicide and/or other forms of death. It is intended for mature audiences. Reader discretion is strongly advised.

It was May 24, 1883. Up until that day, to get from the city of New York (now the borough of Manhattan) to the city of Brooklyn (now a borough in New York City), you had to take a ferry. For fourteen years, residents of the two cities had been watching the incredibly slow progress, hoping against hope for the solution the bridge would bring. Thousands of people gathered for the exciting and historic event. The 21st President of the United States, Chester A. Arthur (who had been Vice President under President James A. Garfield until his 1881 assassination), was there. The Mayor of New York, Franklin Edson, was also there, as was Governor Cleveland. Washington Roebling, son of John Augustus Roebling, the man who originally designed the Brooklyn Bridge, could not attend, but his wife, Emily Warren Roebling, was there. There were even ships gathered in the East River to watch the monumental event take place. It was the day of the grand opening of what was then called the New York and Brooklyn Bridge.

The Roeblings

John Augustus Roebling

It all started with John Augustus Roebling, an immigrant from Germany who was a very successful civil engineer who built wire suspension bridges in America. Roebling was a gifted child, and his mother sent him to study in Erfurt (central Germany) at age 15. Roebling later went to Berlin, where he studied architecture and engineering under Martin Friedrich Rabe, bridge and foundation construction with Johann Friedrich Dietlein, and hydraulics under Johann Albert Eytelwein.

In 1831, he emigrated from Prussia (which dissolved and is now Germany) to Pennsylvania, where he and his brother Carl bought the land that would eventually be the town of Saxonburg. After the birth of his first child and the death of his brother, he left the unsatisfying work of farming and moved on to surveying railroad routes and engineering work, building dams and locks.

Roebling then went on to design several wire suspension bridges, including the Covington – Cincinnati Bridge, now called the John A. Roebling Suspension Bridge, the longest suspension bridge in the world at the time of its completion. Roebling became famous for a type of seven-strand wire rope or cable he invented that influenced the designs of many suspension bridges. In fact, in a posthumous nod, John A. Roebling’s Sons Co. is the cable company credited with being used in constructing the Golden Gate Bridge.

Roebling later perished due to complications from an injury sustained during the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge, one of the first stories that started the bridge’s dark history.

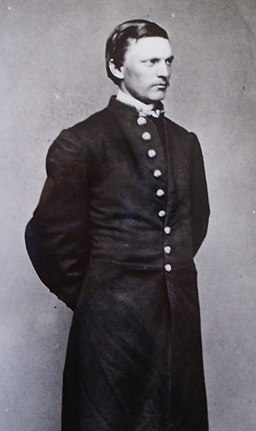

Washington Augustus Roebling

Washington Augustus Roebling was the first-born child of John and followed in his father’s footsteps in the business of engineering. Originally serving as an officer in the Union Army at the Battle of Gettysburg, Washington eventually took over as chief engineer on the Brooklyn Bridge project following his father’s initial injury.

Roebling’s first son designed the two pneumatic caissons for the Brooklyn Bridge, which essentially are the foundations for the towers. While heralded with completing the massive and impressive structure, Washington eventually received a major injury causing him to be an absentee from most of the construction while his wife Emily took over.

His strongest passion was collecting rocks and minerals, and today his massive collection can be found at the Smithsonian Institution.

Emily Warren Roebling

Emily Warren Roebling had spent 11 years totally devoted to the Brooklyn Bridge project, supervising daily work and carrying out the meticulously calculated yet ever-changing plans.

Emily was anything but typical, as she understood advanced mathematics and later taught herself the technical issues needed to assist in the bridge’s construction. This allowed her to take over the supervision of daily operations and perform the duties of chief engineer, which was unheard of, especially for a project of this magnitude. Eventually, Emily would step into her husband’s shoes when he became ill, and she wore them quite well–for more than a decade.

“The Curse” Begins

John Roebling submitted a master plan in 1867 after being named the project’s chief engineer for the construction of a suspension bridge across the East River connecting the two cities of New York and Brooklyn. This bridge would be both longer and taller than any other previously built and would include roadways, elevated rail tracks, and a promenade for pedestrian travel. Initially, the plan was well received in both cities, and people talked excitedly about it being a world-changing event. Two years later, however, people began to criticize the project as either too expensive or too difficult. Not to be dissuaded, John Roebling held what he called a “bridge party” in 1869, inviting other engineers and members of Congress to come and see his other successful suspension bridges and to calm their fears.

In the process of going over the plans with the other engineers, it was determined that the main length of the bridge would have to be raised from 130 feet to 135 feet. This required some other adjustments overall, so John began to conduct the surveys. Taking the ferry back and forth to do so, John was fatefully injured when his foot was crushed between the ferry and a piling. Keeping remembrance of the times, John’s toes were amputated, and as a result, he developed tetanus and then lockjaw, which killed him within a month. This was, unfortunately, just the first of many tragic events to come. The so-called “cursed” project would claim many more lives before its completion.

Washington and the Caissons

After his father died in 1869, Washington Roebling, then 32, was designated as the chief engineer. Tammany Hall, the prominently Irish immigrant-founded organization known for its political corruption, controlled the New York and Brooklyn Bridge Company and approved the designation. Construction began on January 2nd, 1870, with the caissons. Washington Roebling designed these caissons, which are the structures on which the two suspension towers were built upon. (See diagram below.)

The work that then needed to be done was dangerous, however. It involved pumping the space inside the caisson with compressed, pressurized air. Workers would then go into the caisson to dig the sediment below until it sank to the bedrock. At that point, the caisson would be filled with concrete. They worked in the icy water of the East River, but as one worker described it, the temperature was about 80 degrees, and despite the cold water, they were shirtless and soaked with sweat in 5 minutes.

It’s estimated that a total of around 2,500 men worked inside the caissons during this phase due to the high rate of turnover and risk of acquiring what was called “caisson disease” (“the bends”) from working in the pressurized air and rising to the surface too quickly. Workers suffered blinding headaches and also risked paralyzation from the pressure. The Manhattan side tower’s caissons required workers to perform in much deeper water, which meant even more pressure. Washington was himself working in the caissons every day.

The Brooklyn side caisson was constructed in Greenpoint at the Webb & Bell shipyard and was launched into the East River on March 19th, 1870. The Manhattan side launched on May 11th, 1871, from the same shipyard with great excitement coming from a crowd of 3,000 people who took over the shipyard to watch. Several hundred more watched from the piers, nearby building windows and rooftops, and even ships’ decks. New Yorkers in both locations were highly engaged in every major step of building this historic bridge. But before that day, tragedy had struck the seemingly cursed project again: not once, but twice.

The Great Blowout and Washington is Down & Out

During the work being done on the caisson on the Manhattan side, several fires broke out. One, in particular, was called “the great blowout” because it was the most significant and caused about $250,000 worth of damage to the caisson. The timber on the roof caught fire, and subsequent holes had to be repaired, which delayed construction by several months. Repairs were finally completed in March of 1871.

Throughout the caisson work, over 100 men were treated for decompression sickness. Since this condition was unknown at the time, the project physician called it caisson disease. After constantly working in the caissons as well, Washington Roebling himself fell victim to the “disease,” suffering a paralyzing injury. This happened right about the time they broke ground for the tower on the Brooklyn side, and Roebling was bedridden from that point forward. He used a telescope to “supervise” and observe progress from his window but would not have been able to finish the project without his very smart and devoted wife.

A Female Chief

It was at this point Emily Roebling took over for her husband. This was a monumental feat as in the 1800s, women did not generally have the same access to higher education that men did, among other things, and they did not typically study advanced mathematics and engineering.

At first, this just entailed writing and hand delivering instructions and messages to and from the crew, as well as describing to him in detail what was being done each day. But Emily already understood advanced mathematics and quickly learned calculations of catenary curves, strengths of materials, bridge specifications, and the intricacies of cable construction. What she wasn’t sure about, Washington explained in detail for her. Her knowledge rapidly became vast and impressive.

She began spending most of her time on-site, supervising the project in person. In fact, many people assumed she was the one behind the design, especially since she was the “face” of the project. To remain in charge, Washington had to maintain certain aspects of the job, such as appearing in person at the Bridge’s trustees’ meetings. His reputation was questioned when he missed one of the meetings in favor of a trip to Newport, Rhode Island. This was exacerbated by the media, who had discovered the story and called for his termination as chief engineer.

Emily had to lobby for her husband to remain in the designated position of chief engineer. She was well received by powerful politicians and won the right for Washington to remain chief engineer. Emily dedicated the next eleven years of her life to the completion of the project. It’s fair to say that the Brooklyn Bridge would not be what it is today, if not for Emily Roebling.

The Towers and the Curse Continues

The next phase was building the towers. This would prove to be a complex process that took four years to accomplish. It started in mid-1872, and the Brooklyn side was finished first, but both sides were mostly completed by July of 1876. The anchorages could not be completely finished until the main cables were spun. All of this work, on the towers especially, was very dangerous. Even still, there were an unusually high number of accidents that resulted in the death of multiple workers. By 1876, three men had fallen from the towers to their deaths, and several other accidents had happened that resulted in the deaths of nine others.

Even as the death toll rose, another major step was about to be attempted. Temporary cable wires were stretched between the two towers to form a temporary footbridge for the workers while the cable spinning phase was going on. Then, a “guinea pig” was needed to test its strength, so the next step involved sending an engineer across the “traveler wire” in a boatswain chair slung from the wire. Of course, this became another major spectator event, drawing a crowd of at least 10,000 people on both shores. The test was performed without a hitch, to the crowd’s delight.

The temporary footbridge was completed by February 1877. During the time the footbridge was in use, it was briefly “unofficially” opened to the public. A visitor’s pass could be had, and several thousand people from around the world came to cross the bridge within a couple of months it was open. It was closed again when a visitor had an epileptic seizure and almost fell to his death. Perhaps this should have been portentous of the whispered-about curse of the Brooklyn Bridge.

The Curse Strikes Again

The cable work being done was progressing nicely enough, but then tragedy struck again in 1878 when one of the wires slipped, snapping and killing two workers and injuring two others, as well as causing other property damage in the surrounding area. A”well-dressed lady” walking down the street fainted from fright. One of the men died instantly when the steel “rope” struck his forehead and split it open. The other man was struck by a second cable snapping and hitting him in the chest, tearing it open and knocking him backward and underneath the wooden guard rails, where he fell over 70 feet into a gravel yard. Amazingly, though the man was a mangled mess, he was still alive at first. He had broken his arms, legs, and back but (mercifully) did not make it.

The subsequent investigation was incredibly revealing. Back when the cable was being contracted, several bids were received, including the lowest bid, which came from The John A. Roebling’s Sons Company. However, a Bridge trustee who Washington openly did not trust, Abram Hewitt, directed that the contract be given to his friend’s company, J. Lloyd Haigh, instead. Haigh was found to have substituted subpar wire to save money, putting $300,000 in his pocket. Eighty rings of the cable were tested, and only five met standards. Haigh was not fired but was ordered to pay for the better quality wire.

Finishing the Bridge and Opening Day

Construction on the bridge’s superstructure, where the roadways would be, started in March 1879. There was a significant delay of nearly two years caused by one of the companies contracted for steel: Edgemoor Iron Works, based in Pennsylvania. The steel delivery kept getting put off, then blamed on another company. Eventually, after an investigation, things got moving, and the Brooklyn Bridge was essentially complete by January 1883. In fact, it was expected to open in June but was moved up a month. There was still some work being done at that time, but mostly for the pedestrian approaches (entrances ) to the bridge.

On the day of the opening ceremony in May of 1883, Abram Hewitt gave a memorable speech and Emily Roebling waited for her grand entrance, where she would be the first person to “officially” make the trek across the Brooklyn Bridge. She did so in a carriage, carrying a rooster, as a symbol of victory. Washington Roebling held a celebratory banquet at his home that day since he could not attend the ceremony at the Bridge.

People came from all over for the opening ceremony and celebration, and festivities included a live band performance and a fireworks display. That first day, 150,000 people and 1,800 vehicles crossed the Brooklyn Bridge. It had cost the two cities $15.5 million dollars, which today would be nearly $450 million. But the greatest cost was paid in human lives, with no less than 27 people that died during construction, and countless people injured. The problem is, it didn’t stop there.

The Tragedies Beyond

Unfortunately, the tragedies continued beyond opening day, perpetuating what must have certainly seemed like a curse. Just six days later, on May 30th, 1883, a woman tripped and fell down a stairway at the New York approach to the Brooklyn Bridge. As she went down, another woman who saw her fall screamed, which caused immediate panic and an ensuing stampede. At least twelve more lives were claimed, and 35 more were seriously hurt.

During the horrid event, a group started pickpocketing and openly grabbing anything of value, adding to the chaos. In 1885, Rober Emmet Odlum was the first person to jump from the bridge, hitting the water at an angle and dying from injuries. Since then, Brooklyn Bridge has attracted those who are desperately hopeless in great numbers, over time gaining a reputation as a “suicide bridge” that continues to this day.

There have been other notable tragedies on the bridge as well, including terrorist activities. On March 1st, 1994, Rashid Baz opened fire on a can carrying members of the Chabad-Lubavitch Orthodox Jewish Movement. Baz was arrested for his terrorist attack that claimed the life of 16-year-old Ari Halberstam. The entrance on the Manhattan side at Civic Center was named the Ari Halberstam Memorial Ramp in Halberstam’s honor.

While many gave their lives over the course of history of the Brooklyn Bridge, it’s safe to say that NYC would not be the legendary place it is today without it. The historic significance of this bridge is huge and more well known than the people who built it, including Emily Roebling, who paved the way for many future female engineers.

Rochelle Harris is a passionate writer originally from Phoenix, AZ. who credits her success to integrity and determination. She has a great sense of humor, loves music and her family, and writes fiction and poetry in her spare time. She is excited about the New York experience and lifestyle! Follow Rochelle on Twitter at @LinguisticAnRky or get in touch at [email protected]