Homelessness has crippled New York City in recent years, surpassing levels that haven’t been since the Great Depression when poverty plagued the city. Another issue arising alongside homelessness is an increase in adverse weather events due to climate change. The two problems, concentrated in a vulnerable New York City, create a dangerous combination.

Beyond the immediate complications of homelessness, such as health and safety, many wonder what will happen to the expansive homeless population when a new superstorm hits the city, seemingly only a matter of time. With little preparation in place, the answer seems to be a grim one. Below is a breakdown of the homeless crisis and global warming implications and the intersection of the two.

The Homelessness Crisis

According to the Coalition for the Homeless, New York City had 48,413 homeless people in January of 2022, 15,057 of which were homeless children. This figure counts all people sleeping in one of the city’s shelters, but numbers are undoubtedly much higher when including those not in a shelter and not included in the study or count. The 48,413 figure is a single-month count, but during 2021, the number was a whopping and revolving 107,510, an already dreary problem heightened by the pandemic.

In addition to the basic figures, problems amongst the homeless have been increasingly in the news in the last few months as somber stories of deaths. This includes one woman found on a subway train following the loss of her home and the recent hunt for the gunman behind a shooting spree in New York and Washington that left numerous dead.

Additionally, the battle for Mayor Adams to eradicate homelessness in the city has risen to light, concentrating on those seeking refuge in the subway system. But with unsafe shelter conditions, equally unsafe streets, and limited resources, the push for a universal solution leaves many reeling for solutions and no safe haven to turn to in the meantime.

The Climate Crisis

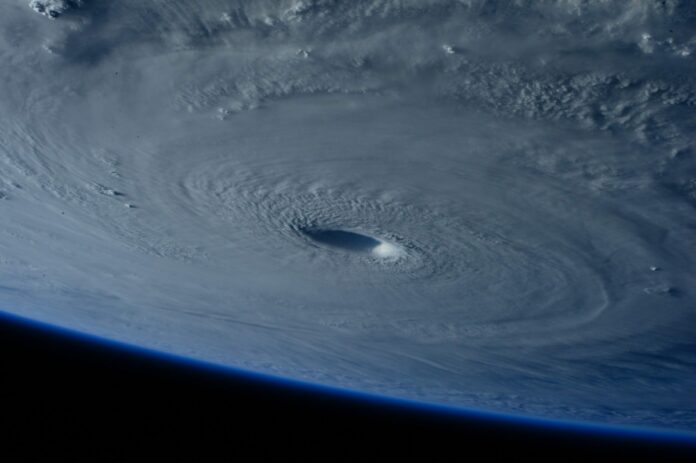

One of the many side-effects of global warming and subsequent climate crisis is that storms are set to increase frequency or intensity. Particularly vulnerable areas include dense coastal cities with rising sea levels and potential for mass floodings, like New York and New York City.

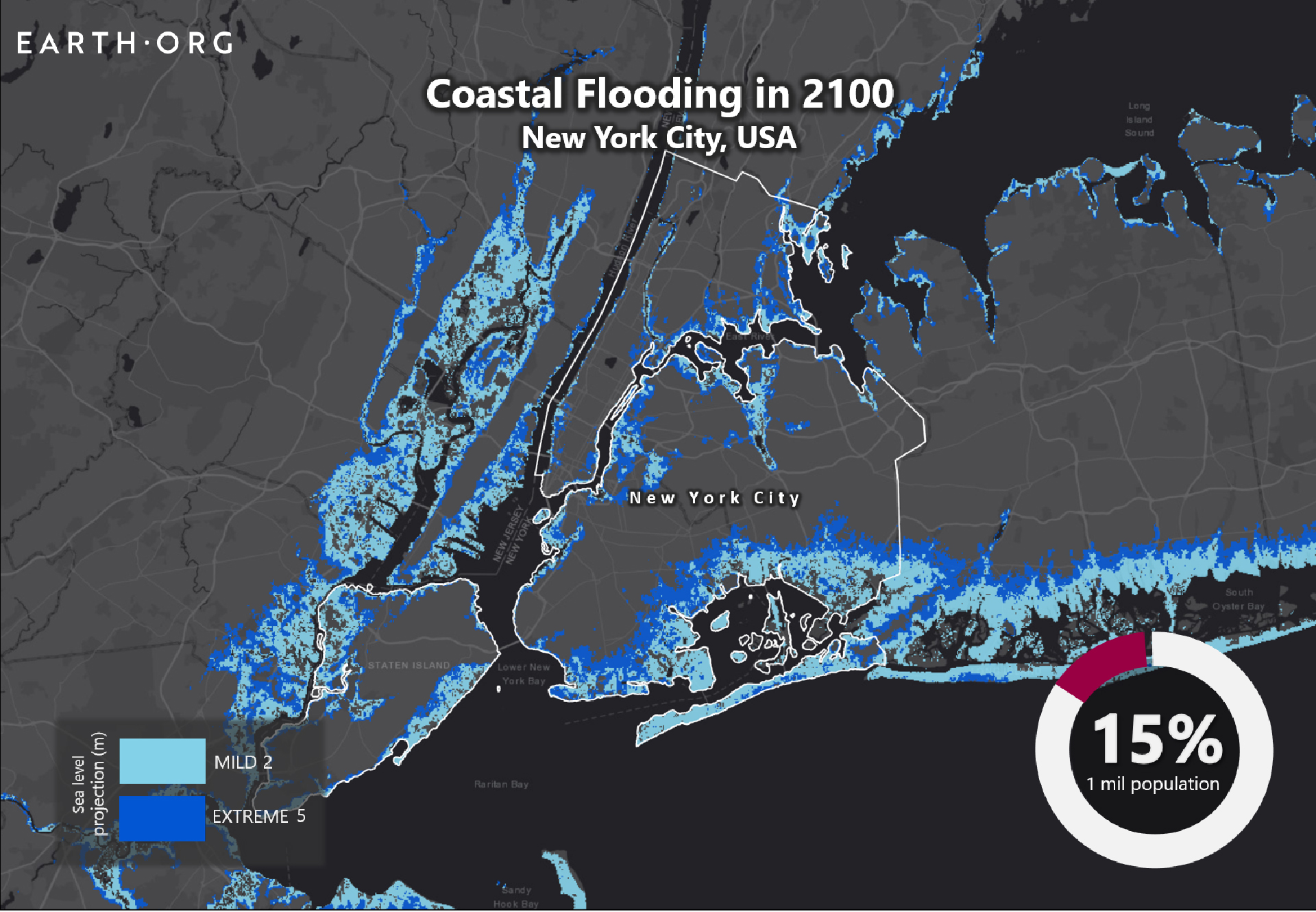

The state boasts 837 kilometers of coastline, and the effects of sea-level rise have already begun to manifest. Rising over 9 inches since 1950, heightened sea levels pose a major threat due to the city’s unique build and density. From the intricate underground railroad system to over half of the state’s residents residing in coastal counties, over 30,000 properties are susceptible to floods and hundreds of thousands of residents.

Earth.Org created a model of New York City and what it may look like with prospective flooding in the year 2100. According to the projections, the areas expected to get hit worst are Long Beach, parts of Queens, including JFK and Brooklyn, Roosevelt Island, and parts of Manhattan lining bodies of water. Across the Hudson River, multiple cities, including Jersey City, Hoboken, and Bayonne, are also subjected to intense flooding, similar to NYC’s current flood map warnings. There is no simple solution, though, with a combination of methods, the area may be able to combat how drastic flooding is – time is running out.

Can New York Sustain Another Hurricane Sandy?

Scientists have thoroughly warned that New York City is not presently equipped to handle intense storming and adverse weather at this time. Even from the average New Yorker’s perspective, the problem is evident in response to storms that were not at full strength.

Looking At Hurricane Henri and Ida

When Hurricane Henri hit on August 22nd and then Hurricane Ida on September 1st last year, the back-to-back hurricanes forced subway closure and mass flash flood warnings. Citizens died, lasting damage was done to the city, and it took weeks to recover enough for things to return to “normal.” Perhaps the single silver lining was that the city’s overall weaknesses and vulnerabilities were highlighted.

In response to these storms, former Mayor De Blasio said, “this is the biggest wake-up call we could possibly get… what we have to recognize is the suddenness, the brutality of storms now. It is different.” Yet, there has been only a slight improvement since those words were said.

Mitigation or Adaptation?

There are two primary types of coping with the already changing climate as total prevention is no longer possible: mitigation and adaptation. Climate change mitigation focuses on lessening emissions to potentially reduce warming and the effects that come from it, such as heavier rainfall and changing habitats.

On the other hand, adaptation works to change the way we operate within our societies and ecosystems to help protect our livelihoods and understand that the changes are inevitable. These adjustments include using sandbags, relocating important buildings inland, and other ambitious preparations.

While programs around the world have taken effect from The Paris Agreement to plans set forth with the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change data, the fact is that particularly vulnerable places like New York, Hawaii, California, and other coastal areas, will need to focus on adaptation rather than solely looking at mitigation via reducing emissions.

That’s because the damage is already present in these areas. New England was deemed to be warming faster than anywhere else in the world at the end of 2021. Sea levels are rising, storms are worsening, the effects are here, and the best thing we can do is prepare, which New York City severely lacks, given its catastrophic potential.

Additionally, the numbers regarding natural disaster displacement are alarming and expected to continue rising, escalating NYC’s homelessness problem. United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction and Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre statistics published via Global Citizen state, “about 14 million people are being made homeless on average each year due to sudden disasters such as floods and storms… The risk of displacement could rise as populations swell and the impacts of climate change become more severe.”

New Orleans vs. New York City

Using the devastating Hurricane Katrina as a comparative example, the homeless population sharply spiked and stayed elevated for years after the event. According to the National Coalition for the homeless, “the homeless issue in New Orleans is problematic. After natural disasters, there is generally an increase in homelessness which ends in about six months. In New Orleans, the rate of homelessness in and around the city has continued to increase, even three years after Katrina.”

For reference, New Orleans’ homeless population in 2018 (13 years post-Hurricane Katrina) was 1,188 PIT (point in time), while NYC’s was 73,523 that same year. If a storm of Hurricane Katrina’s magnitude were to hit New York today, a place with nearly 70,000 more homeless individuals per year, the effects would be undoubtedly horrific, as seen with New Orleans.

New York City’s Current (and Failed) Plans

The city has a Coastal Storm Plan in place that includes a regulated response to any adverse events, especially hurricanes. According to NYC’s Emergency Management, this plan includes,

“scalable, standalone plans that describe the various operational strategies needed to respond to the impacts of a coastal storm. These standalone plans outline such operations as Interim Flood Protection Measures (IFPM), evacuation (including healthcare facility evacuation), sheltering, logistics management, donations, and volunteer management, commodity distribution, debris management, and public information.”

However, these plans seem to target the aftermath and not the minimization of the impact to begin with. Former Mayor de Blasio first proposed a Climate Resilience Plan back in 2019 that would help to correct the shortcomings highlighted during Hurricane Sandy in 2012 directly. The plan initially included a 10 billion dollar budget but was later brought down to a $5 to $7 billion plan. A portion of the funds would target Lower Manhattan specifically by adding barriers, among other tools, for an estimated $500 million. Subsequent ambitions arose of extending land further into the rivers in the lower-lying areas, such as FiDi.

To gain traction for this plan, De Blasio relied heavily on the idea of the Green New Deal passing and a new administration to help acquire funding for the projects, but with the former mayor now out of office and no tangible fruition nearly three years later, some question what, if any, aggressive plans will be implemented and when.

Smaller projects, such as solar-powered streetlights in low-lying areas, have been implemented, but it does little in adaptation. As one of the last things De Blasio formulated on his way out of office, Senator Brian Kavanagh, expressed interest in carrying the torch and hope of developing a similar plan of attack in conjunction with Mayor Adams.

How the Homeless Population Will Bear the Brunt of Storms

Like much of the East Coast, New York City is prone to storms, including hurricanes, tropical storms, and nor’easters. The already devastating climate events are expected to get more dangerous as climate trends continue and have been slowly growing worse thus far.

Encampments and Shelters

Many of the city’s encampments are located in coastal places, and increased neighborhood homelessness complaints are coming in Lower Manhattan or along waterfronts. Without subways, without a shelter of any sort, homeless populations are sitting targets, their entire world vulnerable to being swept away overnight during storm season.

Additionally, even if a person experiencing homelessness were to snag a place in a shelter, the reality is that many of New York’s densest shelters are also in vulnerable areas. This means already overexerted resources and facilities may have the greatest displacement when it becomes necessary to evacuate.

Socio-economic Status and Location

As for those living on the street, where will they go when shelters are maxed out and there is no way out of the city? Pairing flood risk maps with a map of median household incomes in NYC, areas along the water are mixed between high-income and low-income individuals, depending on the borough. Many areas most prone to flooding are overwhelmingly areas with income below $35,000.

That’s not to say that those with high incomes are not also susceptible to displacement. Still, in their choice to live in luxury waterfront buildings, they will most likely have the means to relocate safely when necessary compared to those forced to be in vulnerable areas and will probably be stuck or limited in options when in the path of a storm.

Subways

Subways are particularly vulnerable during these events as their underground nature makes them a perfect place for floodwaters to settle in.

With the uptick in homeless populations seeking refuge in subway stations, the chance of their livelihoods being taken away is much greater—the increased danger of being underground day-round, susceptible at any time to storms.

What is considered an inconvenience for millions of New Yorkers who rely on the transportation system quickly becomes a blatant hazard for those with nowhere else to go, especially in adverse weather events.

Final Thoughts

The reality is that many New Yorkers are vulnerable to potentially devastating storm effects. Storms don’t pinpoint a certain group or have a vendetta. They are largely unpredictable and wild. As they are expected to get worse, the outcomes are too. The key difference is how someone has to react to an incoming storm and preserve their livelihood.

In many ways, the homeless population is especially vulnerable to losing the things they love and are at great risk of losing their lives. To best protect all New Yorkers, it’s necessary to adopt universal adaptation methods while keeping those most vulnerable at the forefront.

Kylee was born and raised just outside of Sacramento in a small town full of history and charm. She stays up-to-date on the real estate market and hopes to empower hopeful buyers and sellers to make the best decisions for themselves. Kylee is particularly interested in bridging the gap for younger generations, helping them understand the power of owning and investing in real estate.