Over half the world, approximately 65%, live in cities, with Paris, Tokyo, and Manila boasting some of the largest populations and population density. By 2050, some experts predict that 7 out of 10 world citizens will live in an urban area, spurring a need for growth, affordable housing, and job opportunities. While over half of the global population lives in a major city, the cities themselves cover less than three percent of the earth’s land, making urban living surprisingly environmentally friendly. New York City boasts the tightest population density of any major city in America, with just over 28,000 people crammed into each square mile in places on average, or in Manhattan, almost 75,000 per square mile. Countless modern advancements have created the “3D” city of skyscrapers and towers, filled to the brim with residents: Perhaps none more than the invention and implementation of the electric elevator.

When was the first elevator built in New York City?

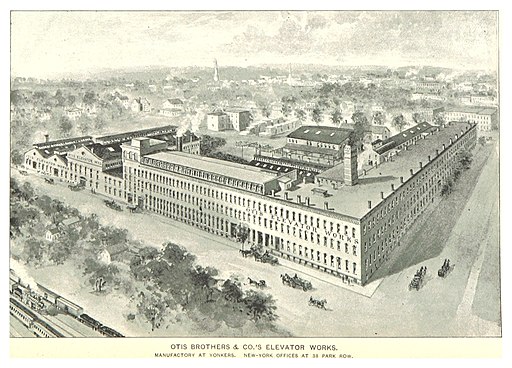

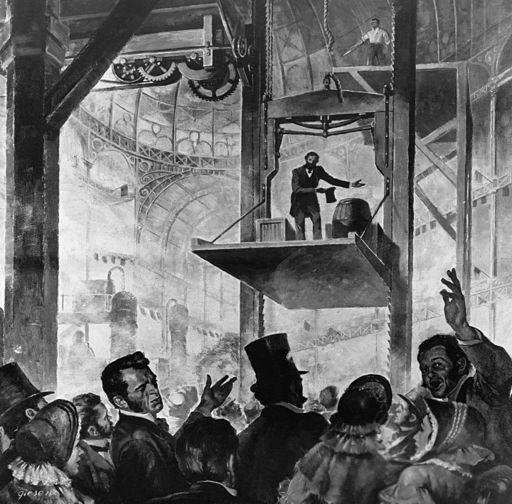

As of 2015, there were approximately 76,000 elevators in operation in New York City. The first commercial passenger elevator in New York, though, could be found in the Haughwout Building, a department store in SoHo. The New York Times hailed the 1857 arrival of the United Technologies/Otis Elevator device as “the beginning of the tall-building revolution.” This original elevator’s appearance and position have never been established. However, it was later replaced in 1892 with another elevator, installed by Alonzo B. See and designed by Freeman and William Bloodgood. The original Otis elevator no longer resides at the Haughwout building, although it does feature one of the oldest operating elevators in the city. Elisha Otis remains a big name in elevators and escalators, having invented the elevator safety brake, which helped standardize elevators by making them practical and safe.

But when it comes to the electric elevator, another name jumps to the forefront of the tall-building revolution, that of Frank Sprague, an inventor with a little-known name but in reality contributed massively to the advancement of infrastructure in America. The 1880s saw the beginning of the Electric Age when Thomas Edison’s central power station opened on Pearl Street in Manhattan in 1882. At the time, the Brooklyn Bridge towered over every other building, the tallest structure for miles. Sprague, who once worked for Edison, opened his own company designing and manufacturing electric motors (now Sprague Devices). This was a massively successful undertaking, and Sprague Motors were commonplace everywhere from textile production to railways such as the Richmond Union Passenger Railway. With his success there, Sprague took his success to Boston and then the rest of the United States, with over 20,000 miles of streetcar tracks crisscrossing cities by 1905.

Were all elevators electric?

At the time, no.

In 1892, Sprague branched out into civilian transportation and formed the Sprague Electric Elevator Company, taking a contract to install his electric elevators in the Postal Telegraph Cable Company building. The terms were strict; Sprague had to install his electric elevators and prove they were more efficient than the hydraulic elevators that were common at the time, such as those provided by industry-dominating Otis Elevators. If he was unsuccessful, the contract dictated the elevators be removed by Sprague at no extra cost. With the stakes so high, Sprague and his contractors waited with bated breath as the Telegraph building finished construction and finally opened.

The elevators were a massive success, and Sprague’s elevators not only functioned efficiently, but they also operated at speeds that ensured you’d be traveling “just as fast” as you would on foot at ground level. In cities like New York, speed is the name of the game; studies show that the length of time spent traveling is more important than the distance traveled when it comes to commuters. This principle applies to vertical travel as much as horizontal, making Sprague’s fast elevators the clear choice over the slower and less cost-efficient hydraulic counterparts. These high-speed electric elevators were exactly what New York City needed to build taller, and a growth spurt followed soon after. Sprague was uninterested, however, in continuing in the elevator business, and after securing several more prestigious contracts, he sold his company to Elisha Otis in 1895, effectively giving the Otis Elevator Company a monopoly on the technology for decades to come.

What was the first skyscraper in New York City?

1913 saw the completion of the Woolworth Building, which at 792 feet tall, was the tallest building in the world until 1930. Its height of sixty stories could be attributed to the high-speed electric elevators that climbed along its spine, eliminating the long waits of older models and the daunting stair-climbing of elevatorless buildings. Elevators created new jobs and industries, creating space for larger factories, taller office buildings, and affordable housing. In addition, the widespread adoption of elevators created an entirely new (if now largely defunct) profession of the elevator operator.

At one point in America, there were tens of thousands of operators, the majority of whom were Black or from other historically marginalized groups. 1917 saw the first elevator operator’s union, offering protections and perks for these highly-skilled workers who oversaw the operation and maintenance of these complex machines. Modern advancements have made elevators easier to use, thus eliminating these positions. However, elevator operation helped lift thousands of workers from poverty and was a very proud profession.

The majority of elevators operating today in New York City top out at the sixth floor, though this may have more to do with water pressure and city fire codes than anything else. New York sits at a relatively low elevation at just 33 feet above sea level and the city’s water is sourced upstate in the Hudson Valley and Catskill Mountains. Gravity works as a natural pump and provides enough pressure to allow the water to be funneled into buildings lower than six stories: above that height, buildings typically require a supplemental water tower or other expensive pump systems. Additionally, newly constructed buildings in the city are required by state law to include an elevator, which means higher prices for potential developers.

Are Elevators Dangerous?

Elevators, while safe, are still subject to many fears and phobias concerning their safety, with over 4% of the world’s population presenting acute anxiety concerning them. That being said, stairs, especially ones with unexpected treads, are actually far more dangerous. The odds of being killed by an elevator are about 1 and 10 million, causing approximately 27 deaths a year in the US. By comparison, falls down stairs account for over 1,600 deaths per year and injure over 1 Million Americans annually.

Elevators also have multiple failsafes that have been added since Elisha Otis’ automatic safety brake. For instance, depending on the building code’s “factor of safety,” elevator ropes (really woven steel cables) must have duplicates and be able to hold 12 times the mass of a fully-loaded car. There are safety precautions called a “safety chain” that refers to a series of automatic checks modern elevators do to ensure safety each trip, ready to cut power to the motor should an issue occur. Issues can include power outages, which trigger one of several clamping-stopping mechanisms to prevent failure. Couple these with the original safety brakes that are still attached to the underside of the cars, and it’s easy to see how modern elevators are actually incredibly safe.

With an approximate combined length of over 1500 miles, there are more miles of elevator shafts in New York City than there are miles of subway tracks (approx 840). Over 35 million trips are taken every day on elevators in the city, there’s no doubt that they are responsible for the shape of the skyline today, with over 260 skyscrapers reaching to the horizon, the most of any US city. At an average time of 118 seconds (nearly twice the average of other locations), elevator rides in New York City give you plenty of time to work on a pitch, prepare for the rest of your day, or maybe just stop and appreciate all of the history and innovation you’re riding in.

Josiah Thomas Turner is writer and musician based out of Washington Heights, New York. Turner received his undergraduate degree in Drama from the University of Wisconsin - Stevens Point before earning an M.F.A. in Playwriting from The University of Texas at Austin. Born and raised in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, Turner trained as a multi-instrumentalist from a young age and spent much of his early years creating and performing music. Josiah’s current interest include animation, video-games and French-Canadian prog-rock.