Several New York City structures pay homage to a distinct architectural style that originated at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Characterized by garish and ornate features, Beaux-Arts architecture was a hallmark of the Gilded Age, a period of great wealth and extravagance in America that lasted from the end of the Civil War until around World War I.

A revival of classical forms and sculptural details characterize the Beaux-Arts style, often in grandiose, symmetrical proportions. While it was born in France in the mid-1800s, it took off in New York City at the turn of the 20th century, emerging as a response to the Industrial Revolution, which had ushered in a new era of mass-produced materials and architecture.

Back then, New York City’s prominent families — Rockefellers, Astors, and Vanderbilts among them — commissioned Beaux-Arts buildings to showcase their wealth and power. In their quest to outdo each other, they engaged in architectural warfare using the Beaux-Arts style. Their lavish mansions and public buildings still stand today as some of the most iconic in NYC.

NYC’s Beaux-Arts Architecture in Action

Pronounced “bo-ZAR,” meaning “fine arts” in French, Beaux-Arts architecture is named for the school in Paris where American architects Richard Morris Hunt and Charles Follen McKim received their training. The architects, who were among the first to bring the style to America, hobnobbed with the elites of their day and helped to popularize the style among the city’s burgeoning rich.

McKim would eventually partner with architects William Rutherford Mead and Stanford White to create the legendary McKim, Mead, and White firm. The firm specialized in ostentatious builds at a grand scale and played a significant role in beautifying New York City, not to be outdone by their counterparts in Paris and other cities across Europe.

McKim, Mead, and White’s efforts yielded a slew of Beaux-Arts buildings and monuments that are a vital part of New York City’s lifeblood, including the Washington Square Arch, the Morgan Library and Museum, and Penn Station, where the style is especially pronounced, with its marble colonnades and Romanesque arches.

Many Beaux-Arts buildings were erected in New York City between 1870 and 1920. While the style has since fallen out of fashion, it’s possible to find a few heirlooms across the five boroughs:

Grand Central Terminal (Midtown East)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Upper East Side)

The Woolworth Building (Tribeca)

The Henry Clay Frick House (Upper East Side)

Washington Square Arch (Greenwich Village)

The Bronx Zoo

Grand Army Plaza (Prospect Park)

Other notable Beaux-Arts structures can be found outside of NYC, including the Vanderbilt Mansion in Hyde Park, Union Station in Albany, and the Electric Tower in Buffalo.

What Makes Beaux-Arts Architecture Different From Other Styles?

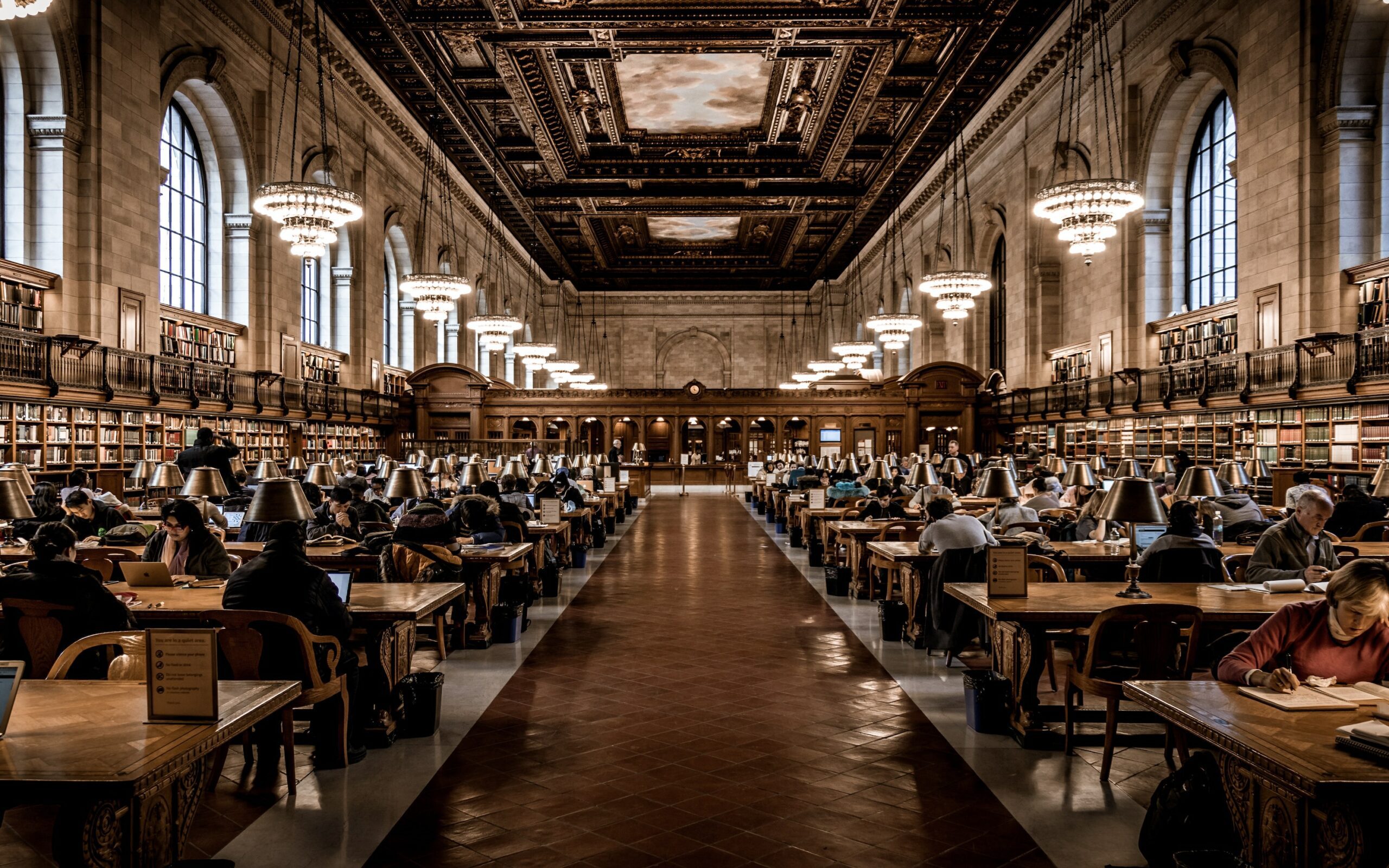

The Stephen A. Schwarzman Building in Bryant Park is an excellent example of Beaux-Arts architecture. Completed in 1911, the building serves as the main branch of the New York Public Library and is one of the most popular landmarks in the city, with millions of visitors passing through its doors every year.

The building’s facade borrows elements from classic architectural styles, namely the Doric and Ionic orders, and is decorated with intricate carvings, sculptures, and bas-reliefs. But what makes it truly Beaux-Arts is the building’s emphasis on symmetry. The entrance is flanked by two stone lions. Further up the steps, a pair of urns (also clad in marble) mirror one another. Even the six figures on the pediment — robed women and men carved out of the stone — dwell in perfect symmetry.

Another distinct feature of Beaux-Arts architecture is its three-dimensional quality, something that is often lacking in other architectural styles. McKim, Mead, and White were particularly skilled at this and would often use sculptural elements to give their buildings an added sense of depth. The original architects of the Stephen A. Schwarzman Building, John Merven Carrère and Thomas Hastings, also used this technique to great effect. The lions, urns, and other sculptures in their design are not just for show. They add to the overall visual impact of the building and help to create a greater sense of space and depth.

In short, those with an eye for architectural detail may detect a building’s Beaux-Arts roots by its emphasis on symmetry and three-dimensional qualities, as well as its classical ornamentation.

What Movement Came After Beaux-Arts?

The Art Deco movement, which emerged in the 1920s and reached its peak in the 1930s, was less about excess and grandeur. It represented modernism, an embrace of the machine age and all that came with it, including streamlined designs, geometric shapes, and new materials like chrome, aluminum, and stainless steel.

While the two styles share some similarities — their use of stone ornamentation, for example — Art Deco was minimalistic and sleek, whereas Beaux-Arts was more ornate and classical.

In Conclusion

After World War I, Beaux-Arts architecture in NYC began to fade away, but its influence can still be seen and felt in many of the city’s famous landmarks. For those who appreciate classical architecture and ornate details, a visit to some of the Beaux-Arts buildings on this list is a must. They’re a testament to the skill and artistry of their creators and offer a unique glimpse into New York City’s rich, storied past.

Ivan Suazo is a copywriter and SEO blogger with over ten years of experience in the real estate industry. He's also the founder of a wellness blog, QWERTYdelight.com, and writes sleep stories for the Slumber App.