From the time the first American cities began climbing up story by story, Black architects have had a hand in shaping our country’s skyline. Their talents and artistry have defined the landscape of cities and universities across the United States, from Los Angeles to New York. Today, let’s take a look at four influential Black architects, all of whom defied institutional barriers to leave a lasting mark on American architecture.

Robert R. Taylor (1868–1942)

Born in 1868 to a shipwright from North Carolina, Robert R. Taylor was familiarized with construction techniques at a young age. He made the decision to formalize his training at the age of twenty and enrolled at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s groundbreaking new architecture program with the class of 1892, subsequently becoming the first Black student to graduate from MIT.

After completing his education in Massachusetts, Taylor returned to the south at the invitation of famous Black educator and orator, Booker T. Washington, to oversee expansions to Tuskegee University’s campus. Taylor went on to design over forty prominent buildings at Tuskegee, including Thrasher Hall, Milbank Agriculture Building, the university president’s home (known as “The Oaks”), and the Butler Chapel, described by Washington as the “most imposing building” on campus. Taylor also played an instrumental role in shaping Tuskegee’s own architecture program, which bears his name to this day.

Outside of his work at Tuskegee, Taylor also designed buildings for Wiley College, Livingston’s College, and Selma University, as well as the Masonic Lodge in Birmingham, Alabama. Taylor died at Tuskegee’s John A. Andrew Memorial Hospital—which he also designed—on December 13, 1942. In 2015, he was commemorated on a United States Postal Service stamp.

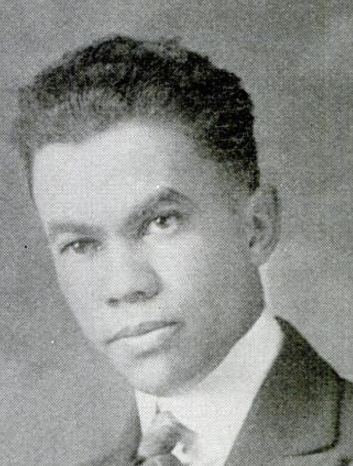

Paul R. Williams (1894–1980)

Paul R. Williams was born and raised in Los Angeles, a city whose landscape he would later define during a long and successful career as architect to Hollywood’s greatest stars. Following his graduation from the University of Southern California in 1919, Williams went on to become the first certified Black architect west of the Mississippi in 1921, and the first Black architect admitted to the American Institute of Architects (AIA) in 1923.

After opening his own architectural office in the city, he quickly became renowned for his drafting skills: Williams famously developed the ability to draw upside-down because white clients often insisted on sitting across from him rather than beside him during consultations. His talents soon caught the eye of Los Angeles’ elite. Over the course of his career, Williams designed private residences for stars such as Frank Sinatra, Lucille Ball, Barbara Stanwyck, and Bill “Bojangles” Robinson. Many of these residences were built in neighborhoods where Black families were forbidden from buying property. Other famous projects in Hollywood include the Stanley Mosk Courthouse, the MCA headquarters building, the Theme Building at Los Angeles International Airport, and additions to the iconic Beverly Hills Hotel.

When speaking of his body of work, Williams recalled the drive that propelled him to success in spite of the obstacles he faced: “I wanted to vindicate every ability I had. I wanted to acquire new abilities. I wanted to prove that I, as an individual, deserved a place in the world.” In 1957, Williams became the first Black architect to be elevated to the status of AIA Fellow; in 2017, thirty-seven years after Williams’ death, the AIA posthumously awarded him its esteemed Gold Medal.

Norma Merrick Sklarek (1926-2012)

Norma Merrick Sklarek’s career began in her native New York City. As the only Black woman in her graduating class at Columbia University’s School of Architecture in 1950, she immediately encountered difficulty in finding an established architecture firm that would give her work. “They weren’t hiring women or African Americans,” Sklarek later remarked, “and I didn’t know which it was [working against me].”

Nevertheless, through relentless effort and determination, she became the first Black woman licensed as an architect in the state of New York in 1954. She later relocated to Los Angeles, where in 1962 she also became the first female Black architect licensed in the state of California. While working in Los Angeles, Sklarek contributed to the designs of major projects such as San Bernardino City Hall, the Terminal One station at LAX, and the United States Embassy in Tokyo, Japan. These great successes resulted in Sklarek becoming the first Black woman to be inducted into the AIA in 1959 and the first to be elected a fellow in 1980.

In 1985, Sklarek co-founded the largest woman-owned architecture firm in the country with architects Margot Siegel and Katherine Diamond. She was keenly aware of her status as a role model for Black and female architects and mentored many such students through their state licensing exams. In her later years, she served as the chair of the AIA’s National Ethics Council, continuing to ensure that architects of all races received the respect and recognition they deserved.

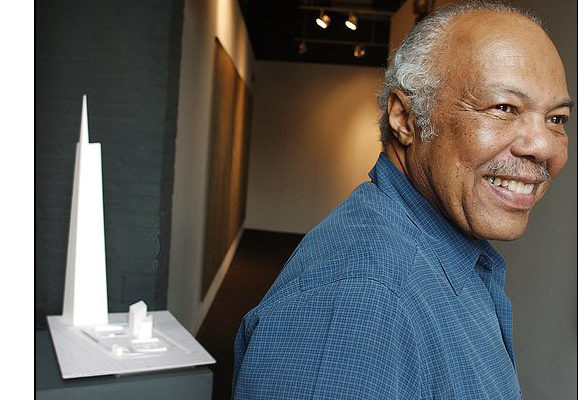

Max Bond, Jr. (1935-2009)

Southern-born architect J. Max Bond, Jr., was partially inspired to pursue a career in architecture after growing fascinated with the design of a staircase he saw at Tuskegee University as a child. He spent the summer of 1956 working under Paul R. Williams in Los Angeles—a breath of fresh air from his studies at Harvard University, where he was told by an instructor that his race would prevent him from ever finding success in his field.

Williams would go on to prove his professor wrong over and over again. After graduating with his master’s degree in 1958, he worked briefly in New York before moving to Ghana, where he worked for the government designing projects like the Bolgatanga Regional Library. Upon his return to New York in 1967, he helmed the Architects Renewal Committee of Harlem, an early and effective advocacy planning organization. With his firm Bond Ryder & Associates, he also assisted in the planning of the Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change, the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, and the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute. His final project was working on the National September 11 Memorial and Museum.

Bond served as an educator for a number of years at both Columbia University and the City College of New York. His architectural outlook prioritized the needs of the community, and he fought tirelessly to ensure that the voices of marginalized people were brought into the rooms where designs were being discussed. As he remarked in a 2003 interview, “Architecture inevitably involves all the larger issues of society.”

Sophie McIntosh is a Brooklyn-based writer and dramaturg hailing from Sun Prairie, Wisconsin. Her plays have been produced by Imaginarium Theatre Company, Platform Production Company, and in the Boston Theater Marathon. Check out more of her work at sophiemcintoshwrites.com!