St. Mark’s Place—an extension of 8th Street that runs from Third Avenue east to Avenue A—is just three blocks long but has had an outsized impact on the culture of New York City. Today the surrounding blocks are an eclectic mix of shops, restaurants, bars, tattoo parlors, entertainment venues, and historic landmarks packed together, frequented by NYU and Cooper Union students and longtime East Village residents. But like all NYC neighborhoods, St. Mark’s Place is in transition, as pioneering speakeasy Angel’s Share and three other nearby businesses prepare to close or relocate due to rising rents. What’s next for St. Mark’s Place? Perhaps its long history holds some clues.

Indigenous Lenapehoking

Before the island now known as Manhattan was colonized by the Dutch, the area around St. Mark’s Place was inhabited by the Lenape people and was part of Lenapehoking, or the Lenape homeland. Lenape people hunted, fished, foraged, and practiced agriculture in Lenapehoking. Modern-day Astor Place, just west of St. Mark’s, was known as Kintecoying or “Crossroads of Three Nations,” a central gathering point between three different Lenape groups who lived in Manhattan in the 16th century and the site where three important trails intersected. Part of one of these trails (which ran from Shempoes Village near present-day Stuyvesant Street and Second Avenue to Kintecoying) passed through St. Mark’s Place.

Petrus Stuyvesant

In the seventeenth century, a mixture of European diseases, land takeover by Dutch colonists, war, and violence either killed or drove most Lenape people from Manhattan. The area’s colonial history begins when the land north of New Amsterdam (present-day Lower Manhattan) was divided into 12 “bouwerijs,” the Dutch word for farm. The largest, Bouwerij #1, was used to support the governing officers of the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam. In 1651 it was sold to Petrus (or Peter) Stuyvesant, the last director-general of New Netherland (the name for the entire area claimed by the Dutch in eastern North America); Stuyvesant’s purchase included two enslaved people. Stuyvesant purchased adjacent acreage, including more of the area now known as St. Mark’s Place. He may have eventually enslaved an estimated 40 people who labored on that land.

Stuyvesant also built a Dutch Reformed church, known as Bouwerij Chapel, on the site of what is now St. Mark’s Church In-the-Bowery. Stuyvesant himself is buried beneath the church, and nearby Stuyvesant Street, Stuyvesant Square, and Stuyvesant Town bear his family name. Interestingly, an enslaved woman named Mayken van Angola and her husband, Domingo lived near the chapel and in 1662 petitioned the Dutch West India Company for her freedom in exchange for doing housework for Stuyvesant. She was manumitted (freed) and may also be buried beneath St. Mark’s.

After the British seized control of New Amsterdam in 1664, Stuyvesant surrendered in exchange for keeping 62 acres of his land. It remained in his family through the American Revolution. In 1793, his descendants sold it to The Episcopal Church for $1. The present building, St. Mark’s Church In-the-Bowery, was consecrated in 1799. Today it is one of the oldest church buildings in Manhattan, second only to St. Paul’s Chapel.

A Fashionable Address?

St. Mark’s Place is an extension of 8th Street. When the city commissioners laid out the plan for the Manhattan street grid in 1811, 8th Street was a demarcation line: streets below it would retain their configuration, as they were too developed to shift to a grid pattern. North of 8th Street, the grid would be adhered to, with buildings and roads shifted as needed.

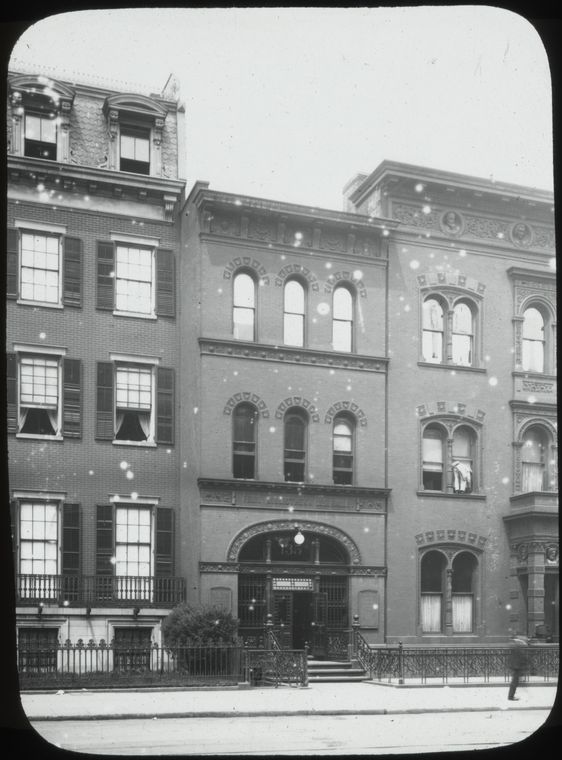

In 1811, however, 8th Street wasn’t developed east of Broadway. The first houses (besides farm buildings) weren’t constructed until 1831-32. These oversized Federal-style homes were built on both sides of the street between 2nd and 3rd Avenues, and developer Thomas E. Davis built them in hopes of attracting wealthy New Yorkers, who were moving steadily north as the city expanded. This is likely why, in 1835, he named the street St. Mark’s Place, after the nearby fashionable church, in an attempt to make it sound like an exclusive address. Two of the original townhouses remain today: number 4 (the Hamilton-Holly House) and No. 20 (the Daniel LeRoy House). However, numbers 25, 20, and 28 also remain but with significant alteration.

St. Mark’s Place never took off as a truly fashionable address, possibly because cattle were driven through it regularly, causing injury to pedestrians. Still, it was home to some famous names. Eliza Hamilton, widow of Alexander Hamilton, and two of her children lived at No. 4 from 1833 until the home was foreclosed on in 1842. Author James Fenimore Cooper lived at No. 6 during the same era. Many more successful but less well-known New Yorkers made it their home: David Hanriques, for example, a Jamaican-born banker who was eulogized in The New York Times as “a gentleman of the old school,” lived on St. Mark’s Place from 1831 until his death in 1859.

St. Mark’s Place residents had easy access to a growing number of important institutions built nearby. Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art was founded at the western edge of St. Mark’s Place in 1859. The Astor Opera House, the site of the Astor Place/Shakespeare Riot of 1849, opened on Astor Place in 1847.

Little Germany

By the mid-nineteenth century, would-be fashionable New Yorkers were moving on from St. Mark’s Place. German immigrants, who came to the United States seeking better economic prospects, moved into the area, turning it into a “Little Germany,” also known as Kleindeutschland or Deutschlӓndle. By 1855 New York City had the third-largest German population of any city in the world, including those in Germany itself. By 1880, 250,000 German speakers called New York City home. Most of those folks lived in the East Village.

With the influx of immigrants came new services, social halls, singing societies, and fraternal organizations, many headquartered on St. Mark’s Place. In 1884, for example, the New-York Cooking School held classes for poor girls (“plainly clad but bright looking girls,” The New York Times reported) in the Wilson Industrial School at 125 St. Mark’s Place. They learned to make an Easter feast of egg and bread dishes. Now it holds apartment buildings and a Starbucks, to many residents’ chagrin.

Today, the most visible remnant of Little Germany is the Deutsch-Amerikanische Schützengesellschaft (German-American Shooting Society) building at 12 St. Mark’s Place. Shooting—specifically target practice and marksmanship—was a popular hobby for an immigrant group that had experienced both the Revolutions of 1847-48 in Europe and the threat of anti-immigrant violence in their new home. The building was constructed in 1888 and features beautiful terracotta ornamentation created by Professor H. Plasschaert, a sculptor. The society’s logo, located on the building front at the fourth story, features crossed rifles and the inscription “Einigkeit Macht Stark,” or “Unity Makes Strength.” The society sold the building in 1920.

The Ottendorfer Library, today a part of the New York Public Library, on 2nd Avenue between St. Mark’s Place and 9th Street is another relic of the neighborhood’s German past. Built in 1884, the library was a gift to the community from successful editor Oswald Ottendorfer and was the first free library in the city.

Elevated train lines opened on both Second and Third Avenue during this time period, with the Second Avenue “El” offering service starting in 1875 and the Third Avenue El beginning in 1878.

Apartments and Boarding Houses

The increased population density of the East Village during the latter half of the nineteenth century led to a shift away from large, single-family homes to boarding houses, apartment houses, and tenements. Other immigrant groups moved into the area. The German population shrank as its members found economic success and moved to less-crowded neighborhoods. Their exodus was sped up by the General Slocum Disaster in 1904, when over 1,000 people, mostly women, and children from the city’s German community, died in a boating incident, leaving the neighborhood grief-stricken and traumatized.

City directories and census lists from the later decades of the nineteenth century reveal St. Mark’s Place as home to both those born in New York as well as immigrants from Germany, Ireland, England, Scotland, Canada, Sweden, Cuba, and Puerto Rico. The street seems to have maintained something of a middle-class character, despite the presence of boarding houses, where many, unable to afford rent on a full apartment, lived. Druggists, physicians, lawyers, journalists, piano manufacturers, carpenters, clerks, tailors, masons, laborers, and manufacturers all called St. Mark’s Place home those decades.

The Little Missionary’s Day Nursery, founded in 1896 by Sara Curry, acquired 93 St. Mark’s Place in 1901. It offered day care, kindergarten, classes, and clubs for neighborhood residents. It still operates today.

The Early Twentieth Century

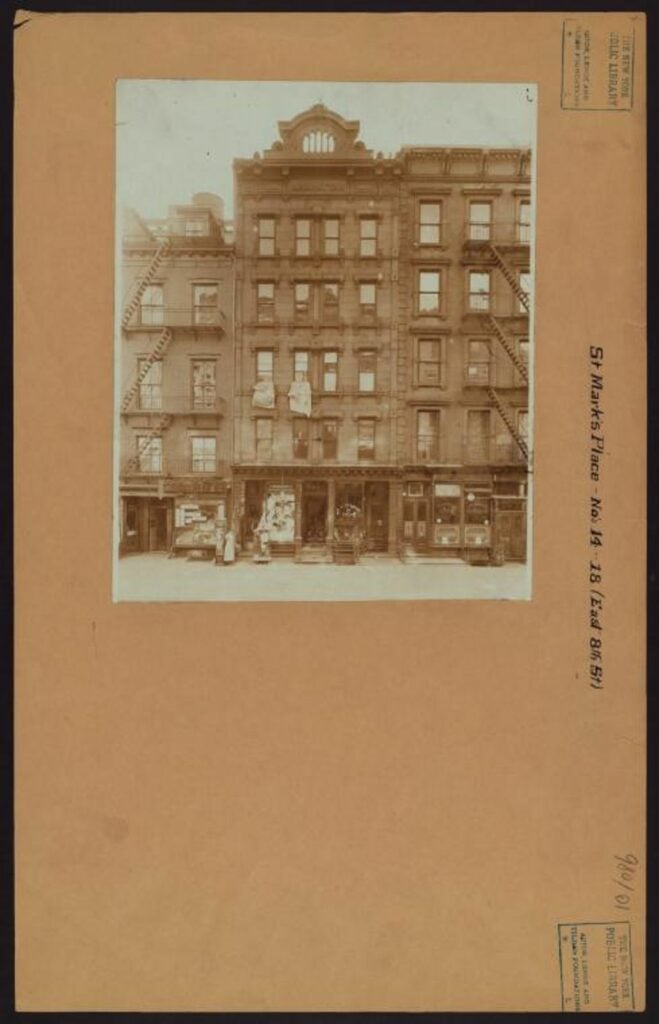

The demographics of the neighborhood around St. Mark’s Place continued to shift as Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe fled violent pogroms and moved to the Lower East Side and adjacent areas. Italian immigrants also began moving to the area. St. Mark’s Place, while home to many, was also a commercial strip frequented by New Yorkers of many backgrounds, with businesses, saloons, drug stores, and restaurants. A photo below from 1910 shows the businesses at 14 – 18 St. Mark’s Place: a cigar store emblazoned “Smoke Telonette,” a clothing store advertising “Furnishings for Correct Dressers,” H.J. Tillman Tailor, The Astor Place Cafe, and 14 St. Mark’s Restaurant.

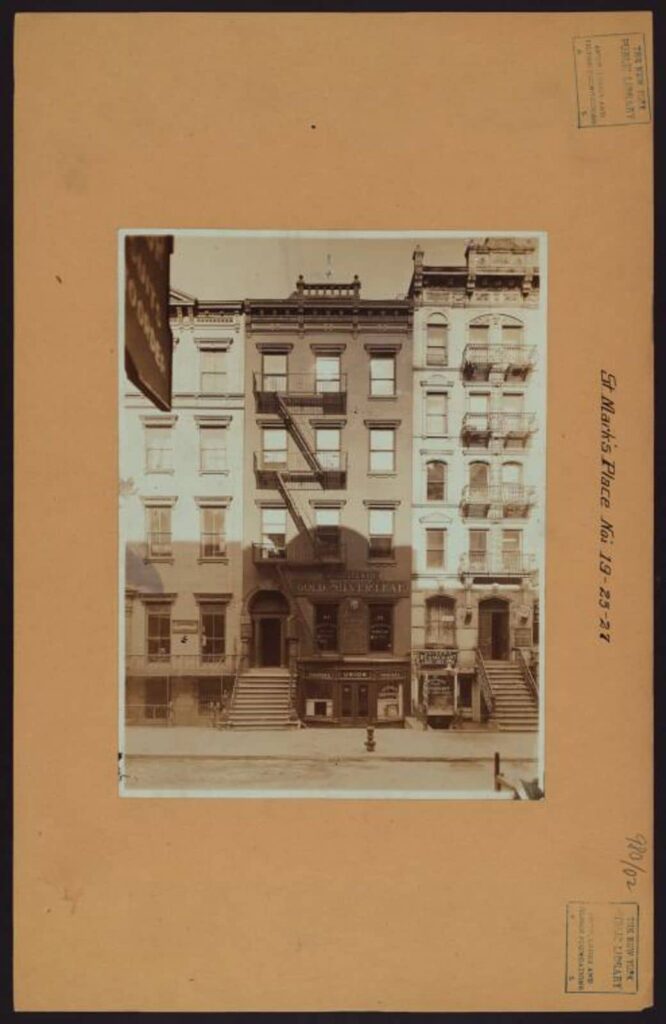

A 1915 photo of 18 – 23 St. Mark’s Place below shows Weiner’s Private Restaurant & Dairy Lunch Room, Schultz & Co Manufacturers of Gold and Silver Leaf, Victoria Printing Co, Cur-o-Pile Paper Co, a ladies tailor and furrier, and the Office of Arlington Hall.

Arlington Hall at 23 St. Mark’s Place was a ballroom used for weddings and parties as well as union meetings and political rallies. It was here in 1917 that the People’s Council for Democracy and Peace, a pacifist group organized in response to WWI, held a rally to oppose conscription. Members of the U.S. Army’s Thirty-First Company, Eighth Coast Artillery set up checkpoints at both ends of the block, ostensibly to allow only as many as would fit in the hall into the area. According to The Sun, a crowd of four or five thousand gathered in Second Avenue as a result. Soldiers and plainclothes cops attended the meeting, then checked all men for their registration cards, arresting fourteen.

This incident shows how St. Mark’s Place was developing as a home for freethinkers, radicals, artists, and intellectuals. Leon Trotsky lived briefly at 80 St. Mark’s Place. The small printing presses in the area, like Victoria Printing Co., produced leftist magazines and newspapers. Anarchist Emma Goldman opened the Modern School at 6 St. Mark’s Place on New Year’s Day in 1911. For ten years the school offered children a decidedly anti-establishment education. This was only the beginning of the street’s countercultural reputation.

Gangsters, Guns, and Gamblers

St. Mark’s Place also saw its fair share of vice in the 1910s and 1920s. In 1900, the Rev. Dr. Charles Parkhurst, president of the Society for the Prevention of Crime led a raid on 9 St. Mark’s Place in order to demonstrate that the cops were getting kickbacks from gambling houses. His raid found 300 men and boys actively gambling, while most police raids of gambling dens found nothing because everyone had been tipped off. (Bizarrely, Parkhurst, a well-known anti-corruption activist, and minister died in 1933 at the age of 91 after he climbed out a bathroom window and off a porch roof while sleepwalking.)

Twelve years later, police themselves attempted a raid on a gambling den on the second floor of 6 St. Mark’s Place. Prevented from entering by an “ice chest door” (the heavy, reinforced front of an early refrigerator), as The New York Times reported, the cops were shot at while attempting to hack their way into the room. Seven men were eventually arrested.

Perhaps most famously, Arlington Hall was the site of a January 9, 1914 “dance” that quickly turned into a gunfight between rival gangs: the Italian gang headed by Jack Sirocco and the Jewish gang headed by “Dopey” Benny Fein. Both men were labor racketeers, and the dispute was over control of the East Side labor unions. The gunfight ended up on the street. A 65-year-old court clerk named Frederick Strauss, a veteran of the Franco-Prussian War and the financial secretary of the Odd Fellows Lodge in St. Mark’s Place, where he was headed that night was shot twice in the head in the melee. He died of his wounds. Only one person was charged in his death: Captain John Sweeney of NYPD was called to account for the neglect of duty that allowed a dance-that-was-clearly-going-to-be-a-gunfight to occur in his territory.

In 1921, 19-year-old Harry Cook, an employee of the delicatessen at 130 St. Mark’s Place, was shot in the heart while on the job in the early hours of November 8. He stumbled outside, bleeding, in view of two cops, but the shooter was never found. The motive was unclear, but there were hints that it was personal. The young man was to be married the next day, and his future father-in-law had helped him buy into a partnership of the delicatessen but may have had reservations about Cook or the business deal.

But perhaps the most terrifying crime occurred in the wee hours—around 4:30am—of October 4, 1925. Max Pfeffer’s restaurant at 25 St. Mark’s Place was full of waiters, coming off shift at the end of a long week with their wages and tips in cash on their persons. Six armed men entered and robbed diners of a total of $9,000. One Julia Kardos, a young woman who worked the restaurant’s pie counter, fainted and was revived by the gunmen who poured cold milk on her head. The robbers sped away as the proprietor of nearby Arlington Hall fired his gun in an attempt to draw the attention of local law enforcement.

Hippie Haven

The Great Depression and WWII years pushed St. Mark’s Place toward decline. The housing stock was old. A June 1935 fire in The Mansion, a social hall at 27 St. Mark’s Place, killed six wedding guests. 82 St. Mark’s Place was condemned in 1938, when a crack in the wall threatened to collapse around residents. An emergency shelter catering to men with substance use disorder opened at 69 St. Mark’s Place (and hosted, among others, a former cornetist in John Philip Sousa’s band). The elevated train lines on Second and Third Avenues were torn down in 1942 and 1955, respectively, cutting off the eastern edge of the neighborhood from mass transit but paving the way for better and more profitable streetscapes.

By the 1950s, cheap rent in the St. Mark’s Place area had begun attracting Beatniks and others who eschewed the values of conventional post-war American life. Poet W.H. Auden and Beats like Jack Kerouac moved into the neighborhood, which was gaining a reputation as Greenwich Village’s rougher, cheaper counterpart. Activists Abbie Hoffman and Jack Rubin lived at 30 St. Mark’s Place, while Lenny Bruce made his home at 13 St. Mark’s Place for a time. Many of these folks patronized Gem Spa, the neighborhood soda fountain/deli/candy store that occupied the corner of St. Mark’s Place and Second Avenue from the 1920s until 2021.

Arlington Hall had become the Polish National Home or Polski Dom Nardowy. The downstairs bar area known as The Dom became a Beat hangout after a local bar proprietor took it over. It was described in a 1965 guide to the neighborhood as “a groovy get-together place for the neighborhood cats and chicks who dig dancing and Polish food at Avenue A prices.” The bar was open from 4 pm to 4 am, with dancing starting at 8:30 pm, and breakfast served starting at 12:30 pm. It was an immediate hit with people from all walks of life.

In 1966 Andy Warhol curated the multimedia show Exploding Plastic Inevitable (featuring Nico and the Velvet Underground) at The Dom. Photos from the event show sharply and conventionally well-dressed young white people. Soon Warhol had transformed The Dom’s upstairs area into the Electric Circus, a discotheque that didn’t serve alcohol because everyone was high on something else. At that point, according to a 1974 article in The New York Times, The Dom became a popular hangout for Black Beats, hippies, and neighborhood residents.

In 1967 500 hippies held a “be-in” featuring bands like The Group Image and Sheila the Slum Goddess on St. Mark’s Place; they planted a tree in the middle of the street that was later moved to Tompkins Square Park. The East Village Other, a local paper, chronicles this era well.

Theater 80, at 80 St. Mark’s Place, opened in a former nightclub space; the building had also previously had a speakeasy/jazz club called Schieb’s. The 1967 world premiere of You’re A Good Man, Charlie Brown put the theater on the map and on secure financial footing; it’s perhaps surprising that a street with St. Mark’s reputation would birth one of the most wholesome musicals in the American canon. (Its next major production was Hair, a more apt choice.)

In the 1980s, Theatre 80, under the same ownership, transformed into a movie theater that screened revivals. It returned to its Off-Broadway roots in the 1990s and continues to this day, though it is facing massive financial challenges in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. The building also houses Schieb’s Place/William Barnacle Tavern, a speakeasy that pays tribute to the building’s past, and the Museum of the American Gangster.

The Dom closed in 1974 and was converted into the Cowpalace, a country-western disco. But during its heyday, The Dom helped make St. Mark’s Place into a hippie haven. The counterculture there was so strong that tourist buses would pass through just to gawk at the street’s denizens. Clothing stores like Limbo opened, offering vintage and second-hand items, especially denim, to shoppers like Janis Joplin and Yoko Ono and inspiring influential stylists. An ice cream parlor called the Ice Cream Connection, which sold drug-named flavors, operated at 24-26 St. Mark’s Place. It later became a longstanding neighborhood eatery Dojo.

Punk Days

The 1970s on St. Mark’s Place was marked by a turn toward punk. Club 57 opened at 57 St. Mark’s Place, a church basement, in 1979. An alternative disco specializing in absurdist theme nights and performance art, it was frequented by artist Keith Haring. Manic Panic, which bills itself as America’s first punk boutique, was opened by sisters Trish and Snooky Bellomo in 1977. Trash and Vaudeville, another boutique, soon followed. St. Mark’s Place had record stores like Freebeing, technically on Second Avenue, and St. Mark’s Sounds at number 20. The neighborhood had a vibrant visual arts scene in those days as well. St. Mark’s Comics opened in 1983 at 11 St. Mark’s Place.

6 St. Mark’s Place, former home of the anarchist Modern School, became a bathhouse in 1915, serving the neighborhood’s immigrant population. By the 1950s, it was a run-down immigrant-focused bathhouse by day, gay bathhouse by night, and became an exclusively gay establishment in the 1960s. In 1979 it was purchased by Bruce Mailman, a theater producer and entrepreneur, who renovated it and reopened it as The New St. Mark’s Baths. The baths were a popular attraction for gay men until they were forcibly closed in 1985 amid the AIDS epidemic.

For a good view of St. Mark’s Place in this era, check out Billy Joel’s 1986 music video for “A Matter of Trust,” which was shot in the old Arlington Hall/Dom space.

A Changing City

Throughout the 1990s, St. Mark’s Place hung on to its downtown character, though that has changed in the 21st century as small businesses across the city have faced rising rents and stiff competition from chains. Coney Island High at number 15 was a popular punk venue in the 1980s and 1990s. It closed when the building was demolished in the early aughts and replaced with condos. 19-25 St. Mark’s Place has been home to both a Supercuts and Chipotle. All the music stores have closed.

Today, St. Mark’s Place is lively and youthful, albeit less “downtown” or countercultural than in the past. The most commercial block of St. Mark’s Place, between Second and Third Avenues, offers many options in Asian fast-casual dining and take-out, catering to the area’s large international student population. Other options for eats include New York classics Mamoun’s Falafel and 2 Bros. Pizza.

For drinks, there’s Barcade, a spin-off of the popular Williamsburg spot, and Irish Pub Bill McCabe’s. Moving further east, bookstore Printed Matter/St. Mark’s is just across Third Avenue in the Swiss Institute building. That block is also home to Porto Rico Importing Co, a coffee and tea supplier owned by the same family since 1907, and the Slovenian Church of St. Cyril.

At the end of the block, you’ll find more options for drinks and eats, including Electric Burrito and Holiday Cocktail Lounge. Crossing First Avenue, the easternmost block offers East Village Books, a neighborhood fixture, and two tattoo parlors, as well bars and restaurants. Here you’ll find Crif Dogs and its hidden bar, Please Don’t Tell, accessible through a phone booth inside the restaurant. The street dead-ends into Tompkins Square Park. Perhaps fittingly, the final establishment on St. Mark’s Place is the symbol of gentrification and chain store takeover itself: a Starbucks.

Leah Reddy is a New York-based writer, video editor, teaching artist, and theatre director/dramaturg with roots on the westside of Cincinnati, Ohio. She’s been lucky enough to teach in all five boroughs of NYC and as a result, spend time in our fantastic city’s lesser-known neighborhoods. An avid runner, foodie, and NYC history buff, she will talk your ear off about her favorite subjects and try to convert you to her level of enthusiasm for the Yiddish Broadway walk of fame, thali, and the fact that Chester Arthur was sworn in as President of the United States in the building that now houses Kalustyan’s. She wants all New Yorkers to be able to enjoy their city and to marvel in the things that surround us all each day.