Today, Chinatown, Civic Center, and the Lower East Side offer a variety of enticing attractions: delicious restaurants, tours of City Hall, and a thriving nightlife scene bring thousands of people to Lower Manhattan each year. But in the 19th century, this area—then known as the Five Points neighborhood—was considered to be a crime-ridden cesspool and one of the city’s worst slums. While very few traces remain of the Five Points, the city’s recent decision to install a street sign marking the former site of the neighborhood will hopefully help to bring more attention to this long-forgotten pocket of New York History.

The Formation of the Five Points Neighborhood

In the early days of colonial New York, city residents enjoyed picnicking by a five-acre body of water in Lower Manhattan known as Collect Pond. As the 18th century wore on and the city expanded, Collect Pond unfortunately became a dumping ground for the waste from nearby tanneries and slaughterhouses, and the pond’s waters were soon polluted enough to become a public health hazard. Rather than attempting any sort of restoration project, the city’s solution was to fill in the pond with earth in 1811 and build over it.

The resulting land was marshy and rife with mosquitos. The buildings erected there tended to sag unpredictably, while the streets ran with mud. Well-to-do New Yorkers avoided the area like the plagues that were purported to flourish in its swampy air, and the neighborhood quickly became known for its extreme poverty. The area was dubbed the Five Points in reference to a unique five-way intersection that occurred at the junction of Cross Street, Anthony Street, and Orange Street, which were later renamed Park Street, Worth Street, and Baxter Street. Today, only the intersection between Worth Street and Baxter Street remains.

Infamy and Criminal Activity of the Five Points

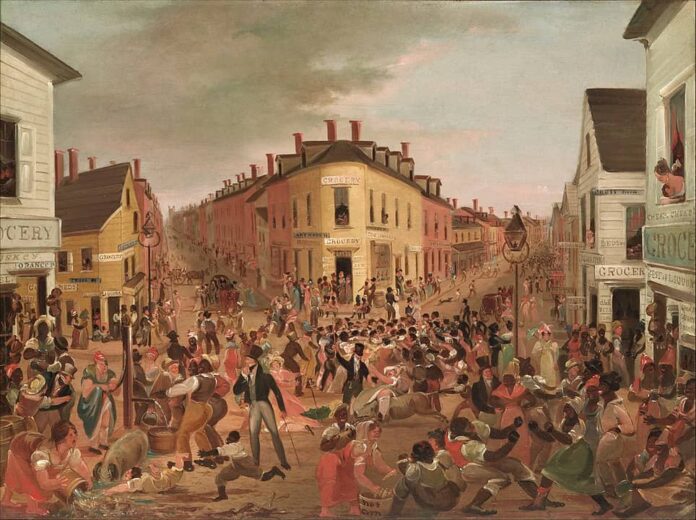

The most prominent depiction of the Five Points in mainstream media comes from Martin Scorsese’s 2002 film The Gangs of New York, which portrayed the neighborhood as a hive of violence and debauchery. Indeed, this is how much of New York—and, as sensationalist journalism became increasingly popular across the nation, the entire country—viewed the Five Points throughout the 19th century.

One major factor that contributed to the area’s crime rates was overcrowding: many residents of the Five Points were forced by their economic circumstances to live in cramped tenement housing. One such tenement, the Old Brewery, was set alongside “Murderer’s Alley” and was rumored to have averaged one murder each night for fifty years. Prostitution was also extremely common across the neighborhood’s tenements.

Gang activity, propelled by groups such as the Dead Rabbits, the Bowery Boys, and the Roach Guards, was rampant across the Five Points. The groups often clashed over territorial disputes and their distinct political agendas—the Bowery Boys, for example, were largely Protestants and staunch anti-immigrant nativists, while the Dead Rabbits were made up primarily of Irish Catholic immigrants. In 1857, the two gangs infamously kicked off a massive riot that lasted two days, involved over 1,000 gang members, resulted in at least eight deaths, and was only squashed when the state militia was called in.

A Historic Melting Pot

While it’s perhaps fair to say that the Five Points fairly earned much of its notoriety, it’s important to note that the neighborhood’s reputation was also heavily influenced by the biases of the wealthy New Yorkers living uptown. The majority of the neighborhood’s residents were newly-emancipated African-Americans and impoverished Irish immigrants, populations that were both frequently discriminated against and banned from seeking high-paying jobs. At this point in history, it was very unusual for these groups to live together in such an integrated manner; in effect, the Five Points came to serve as one of the country’s first true “melting pots.” The city’s elite blamed much of the area’s crime and depravity on the intermingling of races and held up the Five Points as a warning of the dangers of interracial relationships.

The exchange of ideas and customs between African-Americans and the Irish immigrants in the Five Points has had broad cultural impacts that can be felt today. It is believed that the art of tap dancing originated in the Five Points as African-American dancers such as William Henry Lane (also known as Master Juba) began incorporating elements of Irish jigs into traditional African step dances.

However, that’s not to say that relationships between the Five Points’ African American and Irish communities were always civil. A violent week-long anti-abolition protest that erupted in 1834 destroyed dozens of African-American homes and churches in the Five Points and across the city, and the infamous New York City draft riots of 1863 further inflamed racial tensions when the Irish turned their frustrations with the Civil War draft on their African-American neighbors and began a four-day spree of lynching and looting that resulted in at least 119 deaths.

The Dissolution of the Five Points

Sanitation and public health became increasingly important concerns to New Yorkers in the late 19th century as muckraking publications such as Jacob Riis’ How the Other Half Lives—which was published in 1890 and included photographs from within the Five Points’ tenements—exposed the city’s upper crust to the horrific living conditions faced by residents of the city’s slums. Agitation soon began for a massive renewal of the neighborhood.

The planning for modern-day Columbus Park (then known as Mulberry Bend Park) was already underway by this time, and several Five Points tenements were demolished to make way for the park’s opening in 1897. The destruction of the neighborhood’s buildings and tenements only continued over the following years as most were found to be severely lacking in the ventilation and sanitation requirements imposed by 1901’s Tenement Housing Act. After a few decades, the Five Points neighborhood functionally ceased to exist and was subsumed by the rapidly-growing Chinatown—while Chinese immigration to America was curbed by the deeply discriminatory Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, other Chinese immigrants fleeing anti-Asian violence in the western United States relocated to New York in large numbers during this period).

The Legacy of the Five Points Neighborhood

For untold years, one of the only testaments to the existence of the Five Points neighborhood was a single holdover tenement building at 65 Mott Street (which is believed to be the first building in New York specifically constructed as tenement housing). In 2019, however, a New York City historian named Lloyd Trufelman set out to change that. A docent at the Municipal Art Society, Trufelman has long led walking tours of the former site of the Five Points. With the support of the MAS, the Historic Districts Council, and Columbia University’s History and Social Sciences Professor Kenneth T. Jackson, Trufelman successfully applied to have the intersection of Worth Street and Baxter Street “Five Points.” Due to Covid-related delays, the sign was not installed until October 2021.

In the Community Board 1 resolution approving Trufelman’s application, the Board notes that the sign’s installation “recognize(s) the lives of tens of thousands of 19th century Irish, Italian, Chinese and Jewish immigrants as well as the free African-Americans who lived together in this notorious slum where they faced considerable poverty and adversity while helping to make NYC the melting pot that it is today.” The Five Points deserves to be remembered in all of its complexity—not just as a “slum” and hotbed of criminal activity, but as a thriving site of cultural exchange and a place for immigrants, African-Americans, and other individuals pushed to the edges of society to create a community for themselves.

Sophie McIntosh is a Brooklyn-based writer and dramaturg hailing from Sun Prairie, Wisconsin. Her plays have been produced by Imaginarium Theatre Company, Platform Production Company, and in the Boston Theater Marathon. Check out more of her work at sophiemcintoshwrites.com!